Wealth Strategies

Financing Change: How To Invest For Impact - Comment

With so much focus on how people are treating each another, and how companies and governments are behaving in testing times, Earth Day this week is good reminder that climate change and loss of biodiversity are slower-moving trends that we can see coming, and present the larger long-term threat.

Marking Earth Day this week, at a time when the planet is arguably taking a much-needed break from humankind, this guest piece from sustainable private equity investment manager Earth Capital lays out the distinctions between ESG and impact investing, and how impact should be measured in the private market, an asset space in which family offices and HNWs are becoming more involved. The coronavirus crisis has certainly shifted focus away from climate action and those in the thick of sustainable finance are nervous about how much ground will be lost in the race to claw back profits and restart economies at any cost. Like much else at the moment, it's too early to tell.

As an aside, Robeco noted this week that the global carbon project estimates that carbon output could fall by more than 5 per cent this year. (This hasn't happened since the global financial crisis, when emissions dropped by 1.4 per cent.)

The explanation below is also a good companion to commentary published earlier this week from iCapital on how the private capital market has come of age. The editors are pleased to share these views and invite responses. To reply, email tom.burroughes@wealthbreifing.com and jackie.bennion@clearviewpublishing.com

Impact investing versus ESG – what is the

distinction?

Both the agreement of climate goals in the Paris Agreement in

December 2015 and the broader delivery of the 17 UN Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs) from earlier that year have done much to

increase the flow of capital into the low carbon, sustainable and

‘just’ economy, particularly galvanising new investor focus in

impact investing. With this impetus has come a clear recognition

of the distinction between traditional ESG integration and the

new impact investing market.

Impact investing involves making profitable investments with the conscious ‘forward-looking’ intention of generating positive, measurable, social and environmental impact, alongside a financial return. This goes beyond ESG integration which is only a ‘backwards-looking’ reporting of ESG performance, which may still permit investment in industries that can have negative environmental and social outcomes. Impact investing aims to anticipate future societal and environmental needs and deliver positive returns for people, planet and profit.

An ESG integration strategy identifies companies in a sector that performs better than peers in ESG metrics, and implements tilts, exclusions, or active engagement to weight and improve a portfolio's ESG performance. If this is not combined with some form of exclusion-based screening, it may leave portfolios with significant residual exposure to a range of fossil fuel-intensive industries, or sectors like tobacco.

In contrast, an impact investing strategy, takes concrete action by investing in "pure-play" investments focused on actionable positive environmental and social outcomes. Both strategies seek to improve outcomes, but impact investing allows investors to make more focused and measurable contributions. ESG is often seen as changing finance, but only impact investing is consciously financing change.

Private equity for impact investing

ESG integration in large-cap listed equity and fixed income

typically focuses on larger long-established businesses with

significant inertia and long capex cycles. Although ESG data is

becoming available, improvements in environmental and social

performance may be slow, long-term projects. In contrast, private

equity, unlike these other asset classes, is the best approach

for impact investing by giving exposure to

"pure-play" sustainable business models in technology and

services. These offer transformational environmental and social

impact from the outset, with fast-moving business models and

nimble market penetration.

Cutting through complexity in impact

measurement

To date, growth in impact investing has been constrained by the

wide range of definitions and measurements of "impact". The

current wide number of bespoke approaches now needs to coalesce

rapidly around a small number of consistent and understandable

impact measurement standards. We cannot let the perfect be

the enemy of the good. Time is pressing to make impact

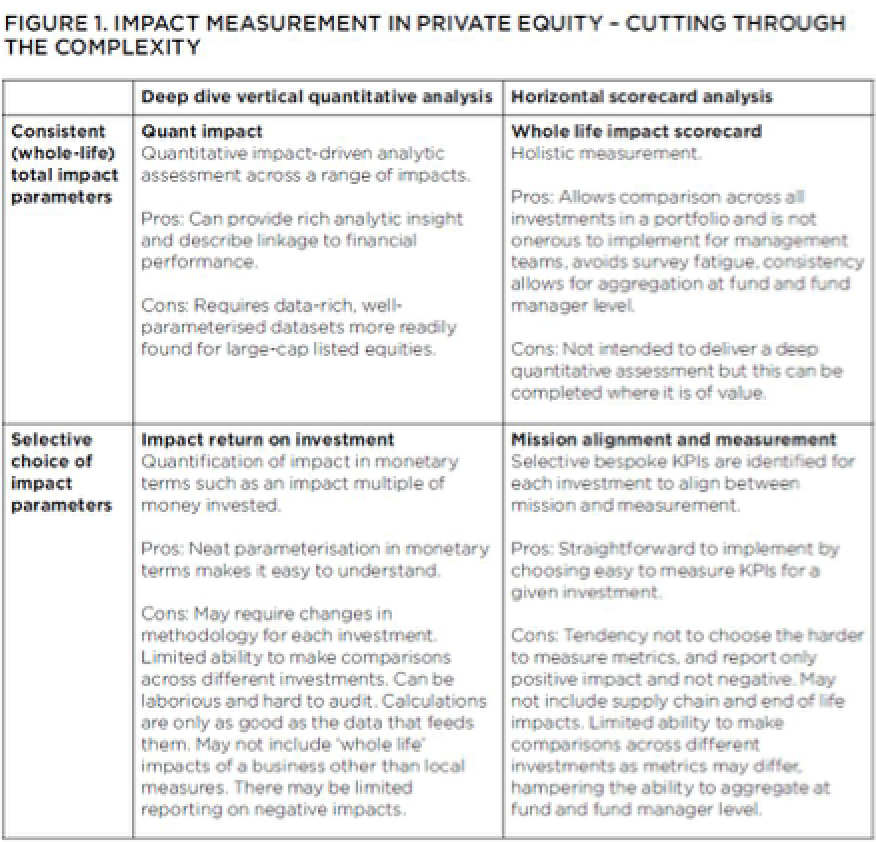

investments. We have reviewed the approaches currently used by a

range of funds and have identified key themes that characterise

different approaches taken. These are set out in Figure 1, which

is defined by two key questions for an impact measurement

approach in private equity.

1. Do you attempt to measure all investments with the same set of

consistent whole-life measures and data sets, or do you select

bespoke sets for each situation?

2. Do you do ‘deep dive’ ‘vertical’ quantitative analysis, or

apply a shallower ‘horizontal’ scorecard approach?

Although the ‘quant impact’ approach is normally only used for

listed equity strategies, the other three methodologies are in

current use in impact private equity. Quantitative analysis such

as "Impact return on investment" can neatly parameterise in

dollar or money-multiple terms, but it is only as good as the

data it is fed and can be complex to implement and hard to audit.

If data is incomplete, its analysis risks becoming spurious.

While the advent of blockchain or ‘big data’ approaches may

assist in these, this remains a future development for private

equity.

Selective "self-certified" choices of key performance indicators unique to each investment are appealing from an adoption perspective but come with significant drawbacks. These "mission alignment and measurement" scorecards may choose only metrics that are easily measurable and look good. This is symptomatic of the trend to report only positive impact and avoid negative.

It is especially vital to include supply chain and end of life impacts in measurement. The 2017 GIIN survey The state of impact measurement and management practice reveals that two-thirds of the impact investment sector only report positive impact, and only 18 per cent measure negative and/or net impact for all of their investments. Even if this is addressed, bespoke KPIs will limit the ability to make a comparison of impact across different investments or to consolidate at fund and fund manager level.

There are several further approaches used in impact

investing

Social impact measurement often uses "theory of

change" models; however, in a "live" investment

environment, the goal setting and measurement involves

effectively the same as the mission alignment and measurement

selective scorecard above, i.e., identify KPIs bespoke to each

investment, and then measure against them.

Control groups are an academic approach to compare investment outcomes against a randomised control group. This can be challenging to implement in many real-world impact investment situations, as a duplicate potential investment must be identified and then kept ‘uninvested’ and measured for the lifetime of the actual investment.

Additionality is also studied in impact investing but its

quantification in real investment situations must be through

either:

a) "Full measurement" approaches which require control groups

with the inherent difficulties explained above, or

b) A KPI scorecard "low, medium or high" which is a subset

of the KPIs in the "mission alignment and

measurement" discussed above

c) SDG based labelling of impact strategies can be used for

high-level sector mapping, but the SDGs do not lend themselves

easily to quantitative holistic impact measurement.

They can, nonetheless, help to define impact metrics for specific target areas.

However, a "whole life" scorecard approach is one we believe delivers consistent and robust impact measurement in private markets. Key performance indicators are selected across ESG tests. The scorecard is easy to implement and is not onerous to complete with portfolio companies. Start of life and end of life impacts are included, and negative impacts are considered and measured. The "whole life" scorecard allows portfolio company improvement to be measured over time, comparisons can be made between investments, and it allows aggregation at both the fund and fund manager level.

Conclusion

Impact investing methodologies will undoubtedly continue to

evolve, certainly in response to rising demand for strategies

that go beyond ESG integration to produce measurable societal

benefits and support a transition to a low carbon, sustainable

and just economy. Initiatives like the International Finance

Corporation’s Impact Management Framework and the

Impact Management Project are invaluable in this

evolution process.

However, the global urgency of environmental and social needs means that impact investment must press ahead at speed. The simple measurement approaches set out in this paper provide the measurement framework to enable this. Private market asset owners and asset managers will benefit from quick and straightforward impact approaches across both existing portfolios and new investments.

The authors of the report are Earth Capital CEO and CIO Gordon Power, chief sustainability officer Richard Burrett, and director of Investment Jim Totty.