Trust Estate

Forced Heirship, Private International Law And Trusts

Forced heirship is a concept that might appear odd to those unused to different legal codes, but it is one that must be understood in a world where more and more HNW individuals have international relationships and assets. This article examines the issues.

As so many HNW individuals and their families have feet in many countries, as it were, the way in which inheritance rules apply in different jurisdictions can create complexity. In the European Union, a Succession Directive, introduced about a decade ago, gave families more freedom about choosing which jurisdiction they wanted for the purpose of inheritance. (The UK was exempted from this, due to its Common Law system that differs markedly from the more Napoleonic approach on most of the continent).

Despite legislative moves, however, the patchwork of rules

can create problems. It is important for advisors to understand

the “forced heirship” rules that apply in certain countries. (It

can mean that a parent must transfer a portion of their wealth to

their offspring, whether they wish to or not.)

To discuss these matters is Jonathan Riley, head of wealth ad the

UK law firm, Fladgate. The views expressed

are those of the contributor and not necessarily endorsed by this

news service. Even so, we are very pleased to share this expert

analysis of a tricky subject. Please respond if you have comments

and email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

Some countries impose rules that determine who may inherit your

estate and in what proportions. These are called “forced heirship

rules.”

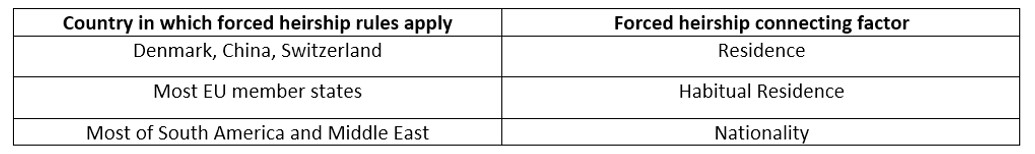

Forced heirship rules can apply to assets in a jurisdiction even

if you are resident elsewhere. The rules can also apply to your

estate if you are connected to a jurisdiction because you live

there or because you are a national of that jurisdiction.

Examples are set out below.

Typically, the rules mandate that your estate will be shared (in

pre-determined proportions) by your spouse and children. Forced

heirship rules are intended to preserve family harmony and avoid

disputes. However, when estates are multi-jurisdictional the

rules can create problems, for example:

-- shares left directly to a child can create a charge to UK

inheritance tax if the deceased is UK domiciled for tax purposes;

-- if property is already owned by family members in different proportions, shares ownership may need to be reallocated following the death which may create avoidable tax, economic and family complications; and

-- dividing a family business in prescribed proportions may

lead to challenging discussions regarding control and

management.

Often the law of the jurisdiction in question enables the

application of these rules to be managed. For example:

-- you may be able to acquire an asset in a way that means a

surviving spouse receives the entirety of the asset on the first

death;

-- heirs may renounce their entitlement (not a particularly flexible approach);

-- you may fall within a “matrimonial property regime” that means on the first death your property passes to your surviving spouse (the forced heirship rules will however apply on the second death);

-- it may be possible to transfer the asset to a company so that you own shares in a company (to which the forced heirship rules may not apply) instead of owning (for example) real estate (to which the rules would apply); and

-- you may consider transferring property out of your estate

– for example to a trust – with the intention that forced

heirship provisions are avoided.

It is important that you and the trustees to whom

you transfer property understand the potential limits of

this final option.

If there are insufficient assets in your estate to satisfy the

claims of an heir, the heirs may claim from a person to whom you

have given assets during your lifetime. This can be a potential

headache for trustees because:

-- if the claim is for a particular asset, the asset may no

longer exist;

-- if the claim is a monetary claim, then the value may have reduced since the gift was made; and

-- trustees will also need to spend time and money managing and potentially contesting the claim.

It might be thought that the “firewall” provisions of the

relevant trust jurisdiction will defeat any claim. Firewall

provisions typically say that the validity of a transfer into

trust (and the trust itself) will be determined by the law of the

trust (not the law of the settlor) with the result that the

transfer may not be challenged. That may be so, but a claimant is

likely to draw on all available arguments to bring their claim.

They may, for example:

-- claim the law that applies to the transfer of the asset

does not recognise trusts and therefore the transfer was invalid;

or

-- argue that the law applying to the settlor prevents the intended transfer and so that the transfer was invalid – this might particularly be the case with a testamentary transfer; or

-- bring a claim as a debtor rather than on the basis that

the transfer was invalid – they may claim the transfer into trust

has defrauded them as a creditor and that in some way the trustee

has been ancillary to that; this clearly is a serious allegation

and one that any trustee would want to avoid.

What then should you do as trustee?

-- Before accepting trust property, always be clear that

your ownership is not likely to be subject to any claims. This

might be one part of your “trust property acceptance” procedure.

-- At each trust review, assess whether any circumstances have changed so that forced heirship rules are in play; for example, have family members relocated to a jurisdiction that applied forced heirship rules?

-- You may ask family members to renounce any claims they have in respect of the trust assets.

-- You should be wary of promoting transfers into trust “as a means of avoiding forced heirship rules.” This might be contrary to public policy in your own jurisdiction and/or constitute an encouragement to defraud creditors.

The interaction of forced heirship provisions and private

international law can be particularly complex in the context of

multi-jurisdictional succession – the above is just the start.

However, much of this complexity can be avoided. Indeed, trusts

can be a very effective vehicle to enable the flexible

application of forced heirship rules but trustees must ensure

that they are fully aware of any changes to family members’

jurisdiction and related asset liabilities.

About the author

Jonathan Riley advises wealthy individuals, their families and the institutions that advise them in respect of their private wealth. He has particular expertise in advising business-owning families. He is recognised as an expert advisor to private clients by both Chambers UK and Legal 500.