Investment Strategies

Diversity: Investment's Central Ingredient

.jpg)

Diversity is often touted as commendable and it is particularly necessary in managing clients' financial lives and not just in simple portfolio terms.

Everyone (well, nearly everyone) likes to talk up the virtues

of diversity. In many cases, this can revolve around issues of

gender, race and ethnicity. But if the 2008 financial crash and

other episodes teach us anything, it is that diversity of

opinions and avoiding complacent consensus, sometimes

aggressively enforced, is also really important. The years

leading up to the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and subsequent

events were marked by a great deal of apparent agreement about

the benign role of central banks, government support for housing,

the reliability of banks’ risk models and value of vast

derivative markets. A bit more diversity about all of these views

might have helped stop the crash.

Diversity, therefore, is a diverse topic. And to write about this

issue from a family office perspective is Christian Armbruester,

founding principle of Blu Family

Office, the European firm. This publication is pleased to

share these insights and invites readers to respond. Email the

editor if you wish to join the debate: tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

Everyone knows you shouldn’t put all your eggs into one basket.

And the word “diversification” is probably the most overused term

in financial marketing since “risk management”. Everyone does it,

everyone has slightly different opinions on how they do it and,

of course, we are dealing with an almost infinite universe of

different products and strategies in a world that is still

random. So how does one really diversify, without getting lost in

the jargon and complexities?

Foremost, we have to look beyond asset classes and the prevailing

model of classifying everything according to stocks, bonds and

alternatives. From a risk perspective, the problem with stocks

and bonds is that both are listed on exchanges. That means both

carry a great deal of so-called “market risk”, which essentially

means, that if the holders of nearly $300 trillion of global

stocks and bonds decide to sell, everything goes down.

The problem with “alternatives” is that it can mean many

different things, from a piece of art, hedge funds or even

venture capital. The other issue is how do you value such an

opaque group of investments or, worse yet, how can you know how

this group of investments will behave when stocks and bonds also

go down?

Our goal is to make sense of this world, in a way that we know

when we want to buy apples, we actually get apples, and not some

strange derivative at an inflated price. No more so than in

finance do you want to get what it says on the tin, and you get

what you pay for. In other words, don’t go into this exercise

looking to do things better or smarter, or that you will in some

way find the holy grail. No one knows.

That’s the beauty of the whole thing and it is what makes it

work, because everyone knows that we can all make transactions

for a price, but we don’t know where that price will be tomorrow

(e.g. no insider trading).

Now that we have left our own hubris at the door, let us explore

what it is we can do to improve the net returns of our

investments. For one, we know we need to avoid losing large

amounts of capital. This may seem obvious to most, but it bears

repeating: it is harder to make back the money that we lost. That

has to do with mathematics, and when we lose 50 per cent of our

capital, we have to make 100% on what is left to get back to

where we started. On the other hand, we have to take some risk,

because otherwise we also can’t make any money. The more we risk,

the more we can earn, so this is also a very personal question

that is best left up to the investor. Most people are comfortable

with losing 20 per cent of their capital to make adequate

returns. Whatever we decide, it’s much more important to make

sure that this is also what we can actually lose, when something

bad happens.

The worst thing we can do, is not knowing how much risk we really

have taken on. If you have deliberately chosen a low risk

investment strategy and commensurately accepted low returns

(maybe for many years), to then lose a large part of your money

on some random event would be suboptimal. The only way to ensure

that we can survive any (random) event, is to allocate our

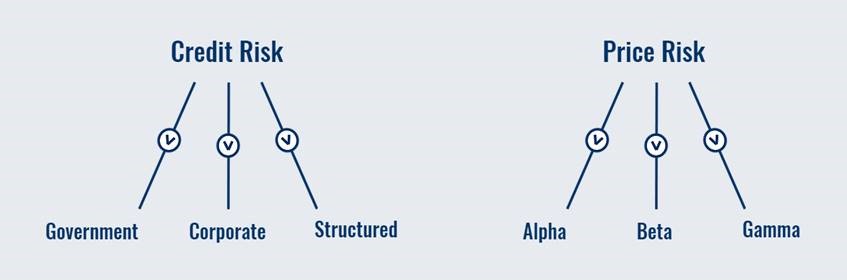

investments into different types of risk. There are only two

basic risks, that of ownership in which case our risk is the

price at which we acquired said asset, and the other is credit

risk, in that we can lend money to others and the risk is that we

don’t get our money back. Stocks and bonds carry these two risks,

but there is no such thing as an “alternative”. There is only

price and credit risk, everything else is a just a form

thereof.

Most popular is the so called “beta” category and this includes

assets such as stocks, commodities, commercial property, or

private equity – anything we buy (for a price), the risk is that

the price goes down. Very different is the infamous “alpha”

category, whereby we take relative price risk and instead of

falling prices, we take views on how two financial assets might

react relative to one another. Often these investments are

wrapped into investment vehicles called “hedge-finds” and so long

as you find managers that don’t take absolute price risk (to

charge high fees), then this form of price risk is very different

to that of the former (beta). Finally, we can also take views on

specific prices (gamma) and this includes speculating on events,

a particular venture or other forms of concentrated risk – all

relating to one price, or an event happening the way we expect it

to, or not. Absolute, relative and specific forms of price

risk by their very nature are different and therefore perfectly

diversify any investments we make to gain upside.

On the credit side, the objective is not to make lots of money,

but to put that what we have to good use and lend it to someone

else. Depending on how sure we are that this someone else will

repay our money, we can charge interest commensurate with the

risk we take on. Most secure are loans to the government, then to

corporations and lastly, we can also lend against the security of

a specific project, asset, or other forms of structured credit

risk. Of course, the quality will vary greatly from one country,

company or project to another. But this is true of everything,

and getting exposure to the various forms of risk through the

best products, managers and instruments is a whole other

story.

Summing it all up, if you allocate your investments across all

the different forms of price and credit risk, your capital will

be protected through true diversification and if you are

efficient in your implementation, you will also be able to keep

most of the returns from the risks you take on.