Investment Strategies

GUEST COMMENT: Understanding Chinese Volatility And How To Avoid Getting Scared

Volatility may be rising in China and there are fears about the solidity of its economy but those concerns should not be exaggerated, argues Matthews Asia, the fund management house focusing on the region.

The following comments were made by Matthews Asia, the

US-headquartered investment house that focuses – as its name

suggests – on the Asia-Pacific region. The views here are

republished with permission. The article’s author, Andy Rothman,

discusses a significant concern about whether rising volatility

will prove a particular headache or not for wealth management

clients, and suggests how people should view it.

Rising volatility in China is a consequence of economic

modernization and should not be feared by long-term

investors.

While it is inevitable that China will, on average, grow a bit

more slowly every year for the foreseeable future, rising

volatility is a consequence of economic modernization and should

not be feared by long-term investors.

Having bet its future on the success of private enterprise, Party

leaders are just now growing comfortable with the idea that

capitalism must allow for failure.

Only 10 per cent of new homebuyers are speculators, with 90 per

cent of sales going to owner-occupiers. And Chinese homebuyers

have a lot of skin in the game: they must put a minimum of 30 per

cent down for a mortgage.

The media reports daily on the increasingly tumultuous state of

the Chinese economy. One private firm goes bust. Another misses a

bond coupon payment.

What great news! Bring on the failures!

Inevitable

While it is inevitable that China will, on average, grow a bit

more slowly every year for the foreseeable future - consider the

base effects and a shrinking workforce, among other factors -

rising volatility does not signal impending doom. Instead, it is

a consequence of important, and largely positive, structural and

philosophical changes underway in China today.

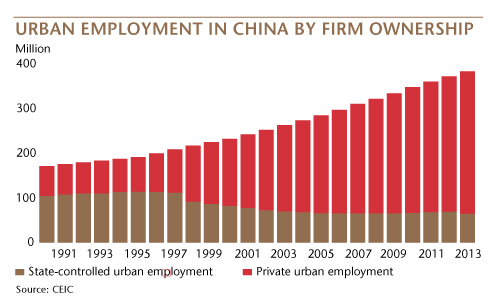

The most significant structural change is the growth of China’s

private sector, which is now the driving force of an economy that

had no entrepreneurs when I first worked there 30 years ago. That

all began to change in the late-90s, when the Communist Party

eliminated 46 million state-sector jobs over six years. That’s

equal to sacking 30 per cent of today’s US labour force, but few

outside of China remember that dramatic start to the reform

process, or understand that those layoffs were accompanied by the

largest one-time transfer of wealth ever seen, as state-owned

housing was handed over, for a nominal fee, to Chinese

workers.

Today, 83 per cent of the urban workforce is private and almost

all new job creation is by private firms. Private companies

account for about 70 per cent of investment and industrial sales,

and the largest share of profits among larger industrial firms.

The state still controls the financial sector and most

capital-intensive companies, but China has become very

entrepreneurial over a very short period of time.

As the economy becomes increasingly market-driven, greater

volatility is inevitable. We know that market economies cannot

avoid periodic recessions, and in the future, this will apply to

China, especially if the Party continues to open up the financial

sector.

This liberalisation should be welcomed by everyone who has urged

the Party to expand economic and personal freedom for its

citizens and its enterprises. Investors have learned to deal with

volatility in developed markets, and they need to do so in China,

acknowledging it as a sign of economic development.

The important philosophical change is the Communist Party’s

recent acceptance of the concept of creative destruction. Having

bet its future on the success of private enterprise, Party

leaders are just now growing comfortable with the idea that

capitalism must allow for failure. As with previous reforms, this

change will be implemented gradually and cautiously.

We’ve seen the first stages of this, as local governments have

apparently been instructed to refrain from bailing out a few

small, distressed private companies.

Death watch

The media has been staging a “death watch” in the city of Ningbo,

waiting for the failure of a single residential property

developer. But, here too, failure should be embraced. There are

probably 90,000 developers in China, although I’d be surprised if

more than 1,000 have more than one project underway. Would it be

that shocking to discover that a few of these firms are poorly

managed, and would fail if the Party didn’t prop them up?

This reflects a healthy and confident evolution of policy and

should be welcomed. This is the kind of change which should, over

the long run, result in a more sustainable economy and a more

open society; the kind of change that should lead to many more

successful, privately-owned, listed companies.

Finally, a few more words about China’s residential property

market, which must be viewed through the lens of the structural

and philosophical changes discussed above. Begin by noting that

the massive transfer of once state-owned apartments represented

the initial liquidity for the ongoing sale of commercially-built

flats that started only about 15 years ago.

Only 10 per cent of new homebuyers are speculators, according to

surveys, with 90 per cent of sales going to owner-occupiers. And

Chinese homebuyers have a lot of skin in the game. About 20 per

cent of sales are all-cash, and owner-occupiers must put a

minimum of 30 per cent down for a mortgage. When investors can

get a mortgage, they must put at least 60 per cent cash down.

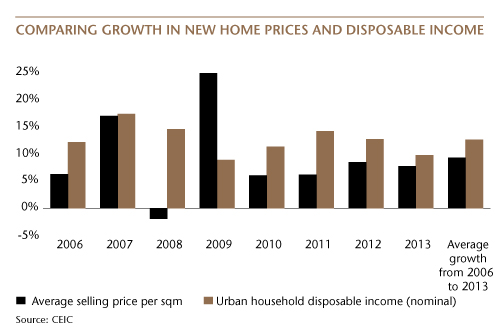

Real estate (residential, office and commercial) has an outsized

role in the economy, including accounting for about a fifth of

all bank loans, but mortgage-backed securities are almost

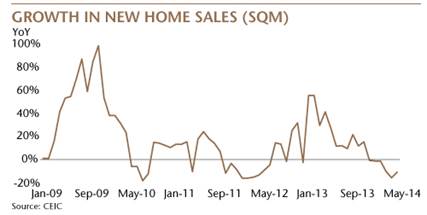

non-existent, limiting significantly the contagion risk of

falling prices. New home prices have risen sharply, by an average

of 9 per cent annually over the past eight years, but nominal

urban income has risen even faster, by 13 per cent per year.

Finally, remember the base. A decline of 9 per cent

year-over-year in new home sales (by volume) during the first

five months of this year sounds far less scary if we know that

sales rose by 38 per cent during the same period last year. Sales

rose by only 2 per cent to 4 per cent YoY during 2011 and 2012,

and the world didn’t end.