Family Office

An Integral Approach to the Family Office - Part Two

Transpersonal psychology and family offices, two seemingly totally unrelated concepts, are relevant to each other, the author of this two-part article argues, examining some of the dynamics that hold families together and also cause potential problems. Here is the second part of the article.

This is the second half of an article from the law firm Squire Patton Boggs on the psychological issues involved with family offices. The article is by from Patricia Woo, who is partner, Hong Kong co-head, at Squire Patton Boggs, in that firm’s family office practice. (To see the first half of this article, click here.)

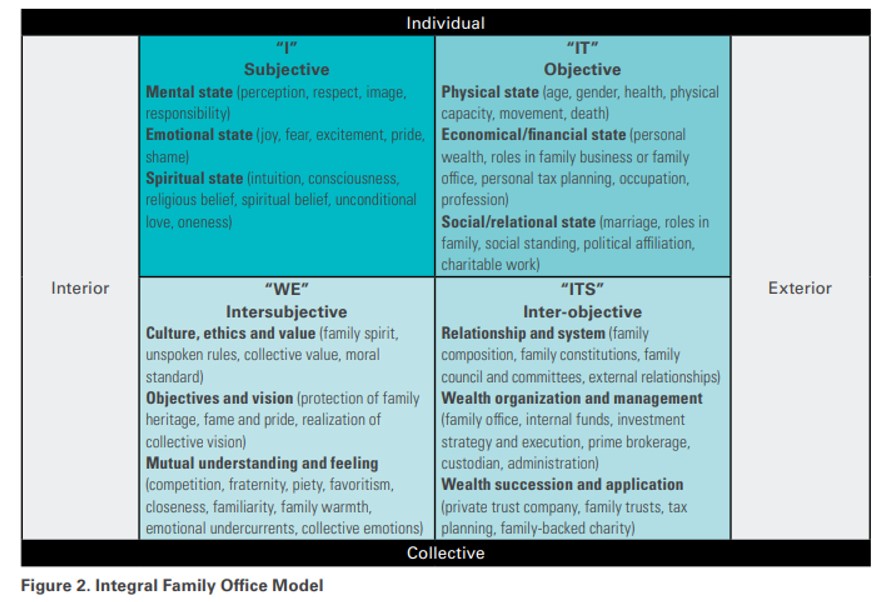

Part 1 of this article featured two tables. To assist readers, here they are again here:

.jpg)

Different family member, different reality

The same framework, when applied to different family members, can

explain the differences in the corresponding reality. A family

member with no active role in the family office, family business

and family council (thus, less active involvement in the

lower-right dimension) might be less engaged and less

appreciative of what is going on in the lower-left dimension. The

challenge for the family office is how to instill in that

individual the sense of belonging. Attending the family meeting

once a year and having an annual distribution from the family

trusts will not achieve much in that respect.

A family leader would have a completely different experience in

the various dimensions. The sense of pride would be higher and

more of his or her upper dimensions would be associated with the

collective perspective in the lower dimensions, especially if

that family is the main driving force behind the family

office.

Does a mentally incapacitated family member have no emotional and

spiritually capacity? Such a family member would have an impact

on other family members, and thus, the other three dimensions in

the model. If some family members have dedicated

religious/spiritual practices, would they feel that particular

aspect of their lives is neglected if the family office only

deals with the tangibles?

Intersubjective dynamics are of such complexity that it is overly

simplistic to assume that the interior “we” is the summation of

the interior “I”s. The essence of the lower-left dimension is

rather “a shared communication and resonance among members of the

group” (Wilber, 2006). This is a task to be facilitated by a

successful family office.

Family offices should go beyond the

lower-right

Most existing family offices, which deal with mainly investment,

succession and family processes on a collective basis, are

creatures of the lower-right quadrant. An internal fund, for

example, segregates the economic interest in the wealth and the

management rights. The family member would have an entitlement in

the wealth in the family’s private fund, but does not have the

right to manage, which is vested in the family office. A family

trust, for instance, is set up to protect the wealth from

creditors’ claims and manage tax costs, but most beneficiaries

are passive recipients without individual participation in the

management and administration. These structures are managed

collectively.

Typical family offices focus on the collective (i.e. the family

as a whole) and the tangible arrangements. There is very little

attention paid to the interior states (e.g. mental, emotional and

spiritual) of the family members. Families are essentially the

family members, and the work of a family office is not complete

if it does not take into account the impact it and its activities

might have on the family members (both externally and

internally).

This resonates with the view of Wilber, who sees that the

medical/insurance and “managed care” industry supports only brief

psychotherapy and pharmacological interventions, both right-hand

approaches, and the interior psychologies are selected against

(Wilber, 2000). Family offices have experienced similar trends.

The investment side and succession planning side (also right-hand

approaches) are capable of demonstrating returns and justifying

expenditure and thus, be more developed than the left-hand

dimensions. However, without the interior, one and his or her

family cannot be complete. This is the time for family offices to

change.

The real meaning of abundance

A client receives an extremely large sum of money from his

father. He knows his father wants him to put the money to very

good use and the client wants to know how he should deploy the

money. My response is that he should resist the urge to invest

for a short while. He is faced with an upper-right stimulus, and

without considering the integral family office model, he would

react immediately by an upper-right action (i.e. making

investments). With this model, we are able to consider the event

with additional dimensions. The lower-right dimension shows a

change in the wealth organisation structure, giving him control

in and/or access to a considerable size of family wealth. A

corresponding change happens in the lower-left, where the family

anticipates passing on not only the wealth, but also the

responsibility and expectation. In the upper-left quadrant, the

sense of responsibility heightens, followed by excitement (and

perhaps mixed with anxiety), and for some, it is the best

opportunity to reflect on not only life purposes, but also the

spiritual and religious purposes.

The best reaction is to take time to “digest” the impact of

material abundance on the person’s internal reality and then make

the appropriate decision, having also considered the impact on

the other quadrants in the model. In this sense, abundance means

not only monetary wealth, but also wealth in the interior and

potential development to benefit the family and the society.

Self-awareness in the family context

A visionary client who is a self-made owner of many international

businesses sees self-awareness as a fundamental process that made

him or her successful. The visionary client wants to instill the

practice of self-awareness in the family. Although the concept

will be included in the family constitution (which is a

lower-right item), the real process happens initially in the

upper-left quadrant and along all three lines of development.

Self-reflection helps one gain clarity in the internal dialogue

of the mind and achieve emotional stability. In a transpersonal

psychotherapy context, it is a process of awakening from a lesser

to a greater identity (Wittine, 1989) and spiritual awakening,

including the practice of self-awareness, reported increasing

over time sense of life satisfaction and wellbeing (Louchakova,

2004). The family office should provide the appropriate

right-hand environment that encourages the family members to

share their reflections and make it a regular practice.

Training, counselling and sharing sessions can be

organised.

Mandatory participation can be potentially tied in with the

legally binding portions of the wealth holding structures.

Forgiveness as a catalyst of development: I discussed forgiveness

in the family office context in an article published last year,

and how this commonly accepted virtue is rarely included in

family constitutions (Woo, 2017). Forgiveness (of self or

another) is a left-hand mental state experienced by a family

member having made mistakes (and usually excluded from being a

beneficiary and an office holder in the family business or family

office). The family member will go through self-forgiveness,

forgiveness by the divine/universe in a transpersonal context and

by other family members who release the anger and decide to

forgive.

The Integral Model, linking a left-hand mental state with the

right-hand reality, provides a roadmap for one to observe and

understand how forgiveness (and healing) happen and can be

encouraged. For a family member excluded from the family system,

he or she could be given a chance to be included again if he or

she proves himself or herself in engaging in impact investing and

charitable activities backed by the family but outside the family

system. These examples in the right-hand dimensions will bring

positive impacts to the left-hand quadrants. When the family as a

whole and its members learn how to forgive, they “transcend the

internal/external distinction” (Lewis, 2005) and leap forward in

terms of the levels of development.

Conclusion

The Integral approach does not guarantee that a family office is

evenly developed in all aspects, but offers the opportunity for

an UHNW family and its family office to be “integrally informed”

of their strengths and weaknesses. The awareness will be the

basis for future development. An integral family office

facilitates not only a more holistic organisation of the affairs

of UHNW families, but also a culture and best practice of

“multidimensional inquiry” (Ferrer, et al, 2005) that best

enables transformation, a process with direct, profound impact on

the self and the family, which “can be the beginning of a

life-long deepening of transpersonal realisation” (Hunt,

2016)

Referenced Works

Caplan, M (2003). Contemporary Viewpoints on Transpersonal

Psychology. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 35 (2),

143-162.

Canda, E and Smith, E (2001). Transpersonal Perspectives on

Spirituality in Social Work. Binghamton, NY: The Howarth

Press.

Cowley, A (1996). Cosmic consciousness: Path or pathology?.

Journal of Social Thought. 1 (2), 77-94.

Daniels, M (2005). Shadow, Self, Spirit. Exeter, UK: Imprint

Academic.

Esbjorn-Hargens, S (2010). An Overview of Integral Theory: An

All-Inclusive Framework for the Twenty-First Century. In S

Esbjorn-Hargens

(Ed.), Integral Theory in Action: Applied, Theoretical, and

Constructive Perspectives on the AQAL Model (pp. 33-64). Albany,

NY: State

University of New York Press.

Ferrer, J, et al (2005). Integral Transformative Education – A

Participatory Proposal. Journal of Transformative Education. 3

(4), 306-330.

Hartelius, G, et al (2015). A Brand from the Burning Defining

Transpersonal Psychology. In H L Friedman & G. Hartelius (Eds.),

The Wiley

Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology (pp. 1-22). West

Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Hastings, A (1999). Transpersonal psychology: The fourth force.

In D Moss (Ed.), Humanistic and transpersonal psychology: A

historical and

biographical sourcebook (pp. 192-208). Santa Barbara, CA:

Greenwood Press.

Hunt, H (2016). The Heart Has Its Reasons: Transpersonal

Experience as higher Development of Social-Personal Intelligence,

and Its

Response to the Inner Solitude of Consciousness. The Journal of

Transpersonal Psychology. 48(1), 1-25.

Lewis, J (2005). Forgiveness and Psychotherapy: The prepersonal,

The Personal, and The Transpersonal. The Journal of

Transpersonal

Psychology. 37(2), 124-142.

Louchakova, O (2004). Corpus Publishing. Awakening to Spiritual

Consciousness in Times of Religious Violence: Reflections on

Culture and

Transpersonal Psychology. In J Drew & D Lorimer (Eds.), Ways

through the Wall: Approaches to Citizenship in an Interconnected

World (pp.

32-46). Lydney, UK: First Stone.

Mahoney, A (2013). The Spirituality of Us: Relational

Spirituality in the Context of Family Relationships. In

Pargament, K I, Exline, J J,

Jones, J W (Eds.), APA Handbook of Psychology, Religion, and

Spirituality (Vol. 1): Context, Theory, and Research (pp.

365-389). Washington,

DC: American Psychological Association.

Sperry, L (2016). Mental Health and Mental Disorders: An

Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being. Santa

Barbara, CA:

Greenwood Press.

Wilber, K (1997). An integral theory of consciousness. Journal of

Consciousness Studies. 4 (1), 71-92.

Wilber, K (2000). The Death of Psychology and the Birth of the

Integral. A Summary of Integral Psychology (Part 1 of 14).

Bounder, CO:

Shambhala Publications.

Wilber, K (2001). A Theory of Everything – An Integral Vision for

Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality. Bounder, CO:

Shambhala

Publications.

Wilber, K (2006). Integral Spirituality. Colorado, US: Integral

Books.

Wittine, B (1989). Basic Postulates for a Transpersonal

Psychotherapy. Existential-Phenomenological Perspectives in

Psychology. New York,

NY: Plenum Press.

Woo, P (2014, October). A Better Family Office. STEP Journal,

70-71.

Woo, P (2017, December). Forgiveness: The Missing Piece of the

Family Puzzle. Offshore Investment Magazine, 16-17.