Investment Strategies

President Trump’s Tariff Strategy: Trade Policy Or Fiscal Reform?

The following article from EFG Bank delves into the US tariff policy to work out the investment implications, and whether such a policy is more about trade or raising revenue.

Far from being just a trade tool, tariffs play a central role in a broader economic vision – one that seeks to reshape the way in which the US government raises and allocates revenue. The article, by Stefan Gerlach (pictured below) chief economist at [tagEFG Bank">EFG Bank, explores the economic impact, and historical context.

The editors are pleased to share these insights; the usual

editorial disclaimers apply. To comment, email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

and amanda.cheesley@clearviewpublishing.com

“We were at our richest from 1870 to 1913. That’s when we were a

tariff country. And then they went to an income tax concept.”

(1)

President Trump supports trade tariffs as a central pillar of his

economic policy, driven by a mix of ideological commitment,

historical nostalgia, and strategic political goals. He and his

advisors view tariffs not just as a tool of trade policy but as a

fundamental restructuring of the way the US federal

government is financed. Their long-term vision is to use tariff

revenue to replace income and corporate taxes, returning to a

system that they claim made America wealthy and powerful in the

late 19th and early 20th centuries.

This view reflects a selective reading of American economic

history. Trump often points to the period between 1870 and 1913

– when the US relied heavily on tariffs and had no permanent

income tax – as a golden age of national prosperity. He

argues that tariffs made the country so wealthy that the

government didn’t know what to do with its surplus revenue.

However, this narrative overlooks the fact that income taxes were

introduced temporarily to finance the Civil War, the economy

suffered severe downturns in 1873 and 1893, and the Gilded Age

– dominated by powerful industrialists – was

characterised by significant inequality and social unrest rather

than broadly shared prosperity.

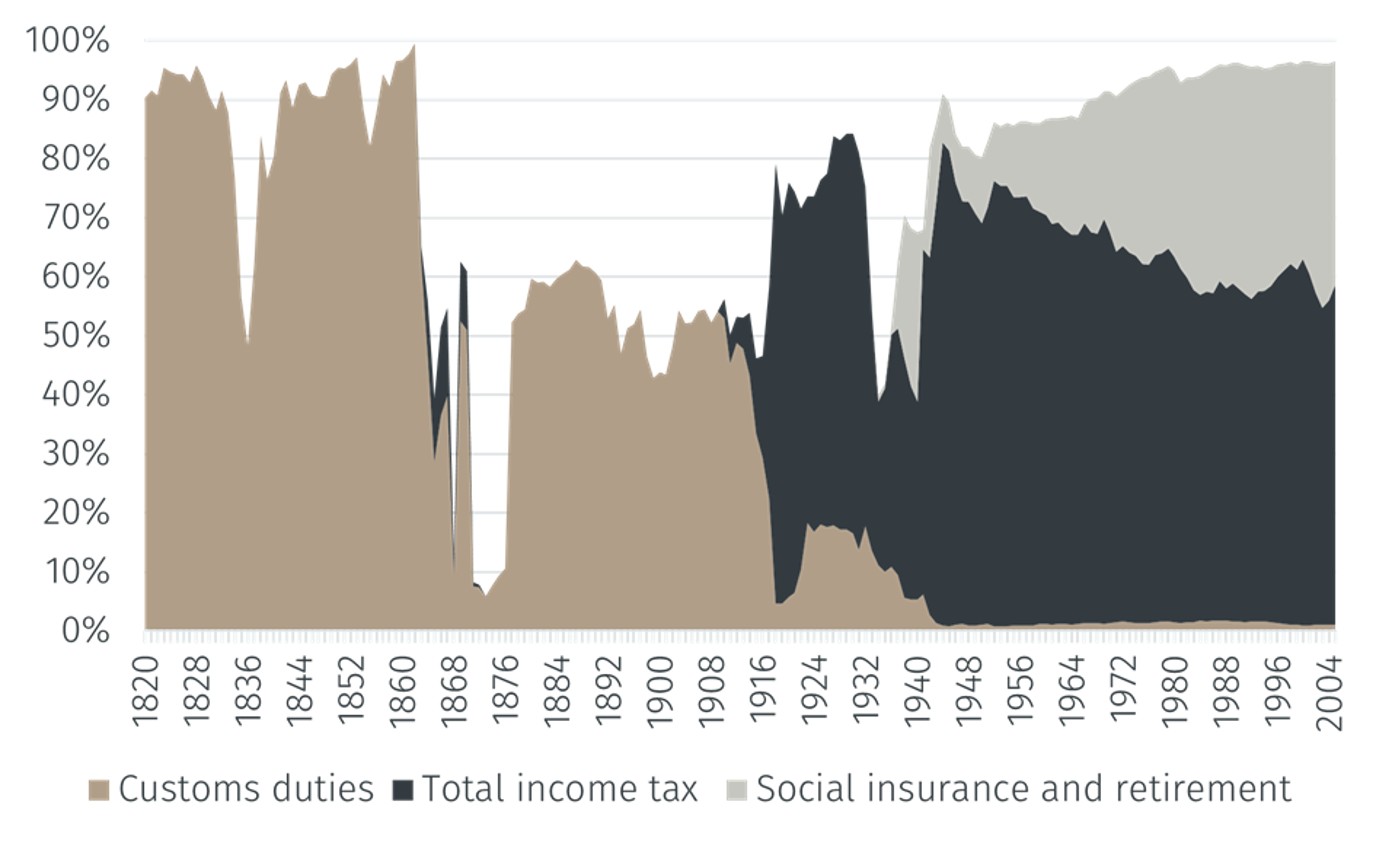

Tariffs were indeed the main source of federal government revenue

in the 18th and 19th centuries, largely because they were easier

to collect than income taxes – all that was required was for

the federal government to control a limited number of ports. The

chart below shows that before the Civil War in 1861 to 1865,

tariffs generally constituted more than 90 per cent of US

government revenue. The rest was sales of public land and, from

1863 onwards, excise taxes.

Source: Congressional Research Service, “US Federal

Government Revenues, 1790 to the present,” 2006.

But the shift towards income tax in the early 20th century

was driven by necessity. The US needed to finance World War I and

to meet the demands of a changing electorate. As suffrage

expanded – particularly to working-class men and, later,

women – political pressure grew for social spending that tariffs

could not fund reliably. Indeed, from 1934 onwards, the US

government raised revenues for social insurance and retirement

programmes. Income taxes were more efficient, scalable, and

progressive, making them better suited for a modern economy.

Tariffs, by contrast, are regressive: they raise the cost of

imported goods, which often hits working-class consumers hard.

While they may seem to target foreign producers, the burden

typically falls on domestic buyers. Moreover, there are limits to

how much revenue tariffs can raise. They follow a Laffer

curve-like relationship: beyond a certain point, higher tariff

rates don’t generate more income, as trade volume shrinks in

response. The high tariffs proposed by the Trump administration

appear unlikely to yield the revenue needed to completely replace

income and corporate taxes.

Trump’s tariff policies also serve political purposes. They

resonate strongly with his base and have helped maintain party

unity, even among congressional Republicans who may have

reservations about the approach. Many lawmakers appear hesitant

to oppose the policy openly, mindful of potential political

consequences. Meanwhile, the administration has pursued

significant shifts in government spending – reducing funding for

certain domestic programmes while proposing increases in defence

spending, immigration enforcement, and border security.

In the international arena, tariffs have also become a tool in

trade negotiations, particularly with China. However, this

strategy has raised concerns among business leaders and financial

markets. Recent market volatility and occasional criticism from

corporate executives reflect growing unease about the potential

economic impact. Prolonged trade tensions, especially when met

with retaliatory measures, carry the risk of escalating and

weighing on both domestic and global growth.

In essence, Trump’s tariff agenda is not just about trade. It is

an attempt to fundamentally overhaul America’s tax system,

government spending priorities, and global economic posture.

Footnote

1, President Trump as quoted by, inter alia,

https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/trump-has-touted-gilded-age-tariffs-an-era-which-saw-industrial-growth-together-with-poverty