Client Affairs

Managing Wealth In Personal Injury Cases

The stakes could not be higher for wealth firms managing clients in catastrophic injury cases.

When UK wealth manager Brown Shipley for the first time named a national head of its Court of Protection business in January, it highlighted how this work is a great responsibility for practitioners.

In the UK, personal injury cases are heard by the Court of Protection. The court assigns a solicitor, known as a deputy, to represent the interests of the claimant. Once the court has established that a claim is to be made, the deputy must appoint a wealth advisor to manage those funds. Then, the wealth manager’s skills and duty of care, and those of other parties, are essential to make sure that vulnerable clients are properly looked after financially.

While issues such as cognitive decline and the needs of an ageing population are gaining more traction among wealth managers, the great responsibility of caring for those whose lives are turned upside down by injury is not always well understood. The stakes are high: the compensation paid in these cases may be the only assets a claimant has if she or he cannot earn a living. As a result, mistakes in asset allocation, for example, will be particularly serious.

This publication talked to Brown Shipley about the wealth angles involved in these cases and also discussed the topic with the law firm Irwin Mitchell. Both parties often work together on claims assigned through the court.

The trend driving demand for these highly specialised services is largely down to progress in healthcare. Medical advances are allowing more people to live longer following serious injury, and equipment and home care is becoming more sophisticated and manageable for many families, which makes it “very important these clients have access to good quality financial advice throughout their lifetime,” Richard McGregor, head of Court of Protection and personal injury at Brown Shipley, said.

No ordinary care

Although McGregor said that the firm’s “duty of care” to Court of

Protection clients differs little from how it manages its main

wealth clients, one distinction is that a clear competence to

handle vulnerable clients must be in place.

“There has to be all the extra checks and balances internally to

ensure the nature of the particular ‘vulnerability’ is well

understood and catered for accordingly,” McGregor said.

“When we compete for business, it’s important we have a sound

asset management record, a track record of service excellence, a

diverse team and that we offer value for money with regards to

pricing,” he continued.

The firm has six teams working across the UK on Court of Protection cases, and while it said that other managers also work in the personal injury space, few have teams working exclusively to safeguard this type of client, particularly at the level of dedication and commitment needed.

To explain the intricacies of managing the financial wellbeing of a person living with severe injury, Brown Shipley provided the case study of Rob (not his real name).

Rob is 22 and has a life expectancy of 72 years. His yearly expenditure is £175,000 ($230,735), and his needs are expected to significantly rise in the coming years, creating a potential shortfall. To ensure that Rob’s net annual return continues to meet his long-term needs without creating unsustainable levels of volatility in his investment portfolio, the firm calculates that a relatively small cost cut allows it to extend the life of his funds significantly, and within an acceptable level of risk.

“Given the 50-year timeframe for Rob, the re-calibration of the cash-flow modelling at annual review meetings and the investment risk management approach was crucial,” McGregor said. The team also worked closely with Rob’s deputy and gained input about his care and equipment needs from his case manager, he continued.

“A high level of expertise and experience, giving insight into Rob’s needs, was integral to us getting the right outcome,” McGregor said.

Brown Shipley also often acts on behalf of children who have suffered serious injuries and require complex support structures. Associated planning in some of these cases has to support a life expectancy beyond 60 years, with annual costs running into hundreds of thousands of pounds.

“Taking into account inflation, much of which is wage related for carers, and potential changes in circumstances whilst managing liquidity and minimising investment risk, it can be a very fine balance that requires a highly specialist approach,” said McGregor.

Legal duty of care

Julia Lomas, who oversees nine national Court of Protection teams

at Irwin Mitchell, said that supporting clients in cases that go

through the CoP is one of the most important aspects of the

service it provides and accounts for a significant proportion of

her department’s case load.

A 20-year practitioner and partner at the firm, Lomas said that the financial planning side of the job is as critical as investment performance. “The main objective of successful Court of Protection work for both the deputy and wealth manager is to ensure the effective management of a client’s damages settlement in order to improve their quality of life and last for the duration of their lifetime,” she continued.

In personal injury cases, the first phase of these claims is to establish liability, i.e. whose fault it was and then, how much will they receive in damages. Also “the issue of split liability can significantly reduce a claimant’s damages so it is important that the deputy has a solid understanding of the case at hand,” Lomas said.

Legal commitments include staying up to date on a client’s needs and any changes in their health or other personal circumstances. The firm holds a yearly face-to-face meeting with the wealth manager to look at an update of the client’s investment performance over the last 12 months, and the two teams work together with other professionals to identify priorities for the coming year.

“In the case of catastrophic injuries, the claim solicitor will often seek interim payments for their client so they can begin rehabilitation as soon as possible. Once a final settlement has been agreed, which in some cases can take several years, a wealth manager would then get involved to help manage this sum,” Lomas said.

A deputy typically composes a shortlist of IFAs/fund managers before inviting them to take part in a face-to-face ‘beauty parade’, in which “firms will be quizzed across a number of areas”, said Lomas.

Firms will be questioned on how much of the settlement figure they would invest, what their risk profile looks like, the extent of their total expenses ratio, the possible use of onshore and offshore investment, asset allocation, and how they benchmark themselves and performance details over the last one, three and five years.

In turn, the work done by deputies for claimants is overseen by the Office of the Public Guardian, which “carries out assurance visits on deputies and looks at their investment processes,” Lomas said.

Legally, deputies are bound under the Mental Capacity Act (2005) in their dealings with a protected party, which often means involving them in financial planning and decisions.

“The potential complexity of the cases that solicitors deal with and the responsibility they hold cannot be overstated,” said Brown Shipley’s McGregor.

One change Lomas has witnessed in personal injury cases is a shift from the traditional lump-sum payment structure to increasing numbers of annual periodical payments being awarded to claimants. She says this is largely down to external factors, such as medical advances, longer life expectancies, and the impact of inflation. It “means that regular payments over the long term are sometimes better suited to meet the needs of clients for the duration of their lives.”

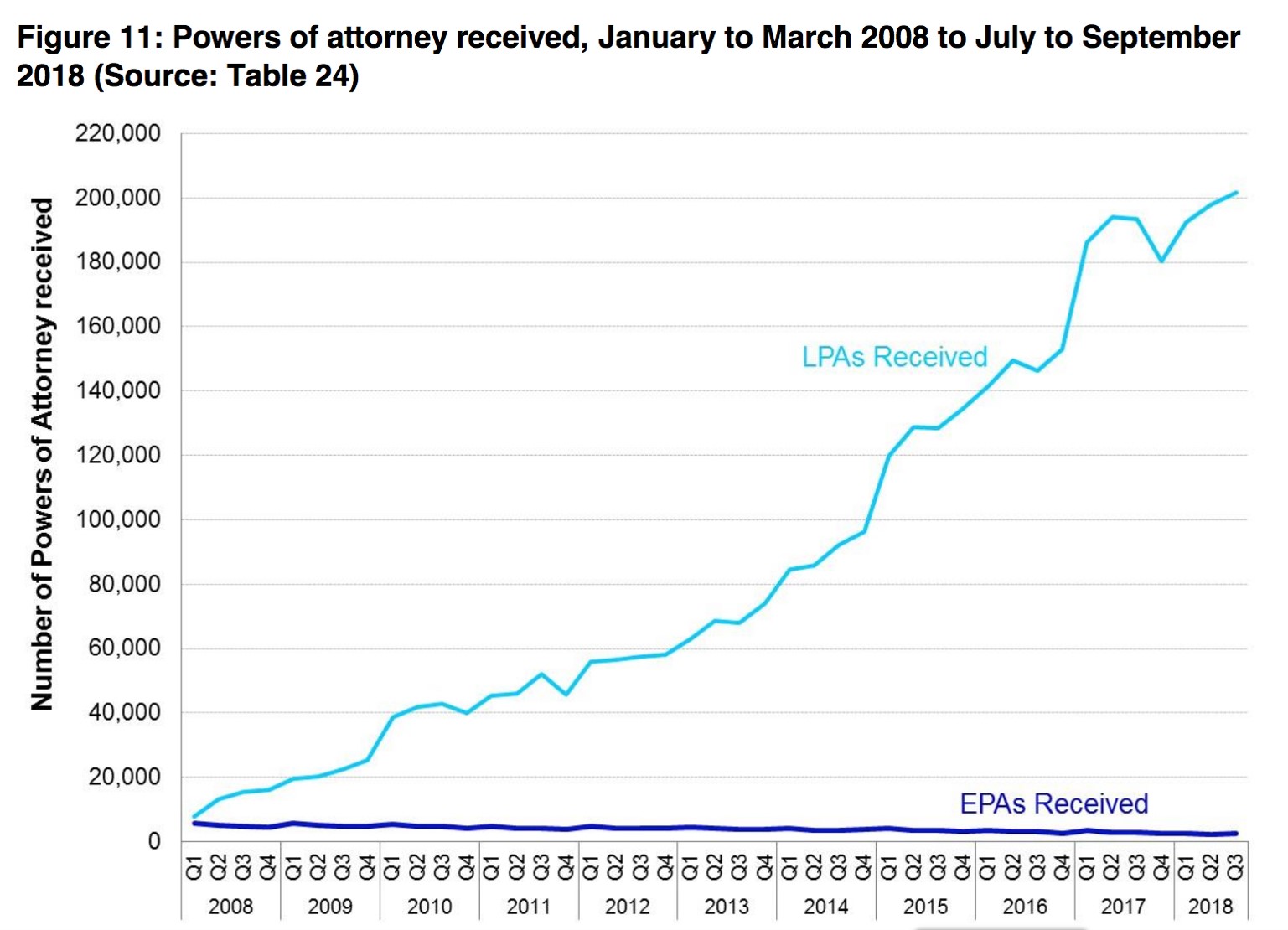

Here is a graph showing powers of attorney received:

The role of the CoP, Lasting Power Of

Attorney

While the Court of Protection deals with a significant number of

claims for catastrophic injury each year, most of its casework is

involved with elderly people who have lost the capacity to manage

their affairs. At this juncture, families can apply to the court

for a Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) to act on their behalf –

these cases often involve ageing parents living with dementia.

According to the latest meeting of the Court users' group in October last year, the volume of applications processed through the Court of Protection went up by 3 per cent in the six months to April 2018, which does not surprise Lomas given the UK’s ageing demographics. During the last 10 years, however, LPA applications have risen sharply from under 20,000 received in 2008 to more than 200,000 received towards the end of 2018.

The rising number of LPAs issued by the court has stoked the ire of advocates and practitioners who fear a lack of transparency and the potential for abuse by unscrupulous family members and similarly by rogue legal professionals, which is leaving old people even more vulnerable.

Asked for her views on the increasing use of LPAs, Lomas said that replacing the Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) with the Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) in 2007 has certainly extended the reach of these powers.

“Split between financial matters, such as property and affairs, and medical decisions, such as health and welfare, alongside the wider context of an ageing population, it is no surprise that many legal firms are actively promoting the benefits of such applications.

“While I certainly see the advantages associated with said powers, opinion is divided across the industry. The former Court of Protection Senior Judge, Denzil Lush, for instance recently stated that he personally would never sign an LPA due to the “devastating effect” they can have on family relationships as a result of lack of transparency around them.”

Critics point to the weakness of the Court of Protection in conjunction with the Office of the Public Guardian in investigating LPA abuse.