Investment Strategies

GUEST ARTICLE: The Wealth Of Nations

This article looks at some potentially troubling long-term economic trends and what they mean for future prosperity.

In this article from Subitha Sabramaniam, chief economist at

Sarasin & Partners, the author takes a step back from some of the

more immediate issues, such as Brexit, deceleration in China or

the state of monetary policy, to look at longer term economic and

social trends in many economies. Wealth managers, when they

allocate clients’ assets and consider the kind of goals clients

have, must sometimes be willing to take a wide view. We hope this

article is of interest to readers and invite

responses.

Janet Yellen, the chairwoman of the Federal Reserve’s Board of

Governors, has been extraordinarily cautious about raising rates.

What is worrying her? For sure, the economic recovery from the

depths of the financial crisis has been lacklustre; but

recoveries after deep credit crises are typically anaemic. Over

the past seven years, unemployment in the US has steadily

declined and while inflation might not be roaring ahead, it is

comfortably within the reaches of its midterm mandate.

So, why is she concerned?

A central bank today is very much a post war institution – built

to navigate a world of supportive demographics and successful

innovation waves. For much of the past 30 years, the prevailing

dogma has been that if policymakers focused on price stability

and minimised cyclical volatility, a country could comfortably

achieve its economic potential. Economic growth would follow its

pre-ordained trend built upon demographics and innovation.

In recent years, however, demographic forces have weakened

considerably and labour productivity seems mired in a post-crisis

torpor. With many inexorable trends grinding to a halt, Yellen’s

caution stems from a concern that the listless economic recovery

represents a deeper economic malaise - one where the cyclical

recovery is struggling to gain momentum because of a downward

shift in trend growth. In such an environment, it is exceedingly

difficult to extricate cyclical impulses from a shift in trend

and harder still to assess the "natural rate of

interest" for the economy.

Adam Smith, in his sprawling work, An Inquiry into the Nature

and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, postulated that a

country’s output is generated by its workers and in proportion to

their productivity. Over the years, his thesis has become one of

the central principles of classical economics. Every year,

individuals, businesses and policymakers invest sizeable

resources in generating, managing and measuring the flow of

output (gross domestic product) that stems from the country’s

workers. Financial markets, which reflect the profitability of

such enterprise, ebb and flow with the rise and fall of this

measured output.

While short- and long-term investors have distinctively different

approaches to identifying investment opportunities, both are

driven by the flow of output. Short-term investors are more

likely to try to arbitrage short-term deviation of output from a

long-term trend, while longer term investors are likely to focus

on the trend itself. For all investors, though, clarity over the

long-term trend is critical.

So, how do we estimate the long-term trend?

A common approach is to use an average over a long time period.

There are good reasons for this. Advanced economies like the US

or the UK, which are considered to be at the technology frontier,

have an "organic" rate of innovation. This is the pace at

which they create and synthesise successive innovation waves. It

is the pace at which standards of living typically improve.

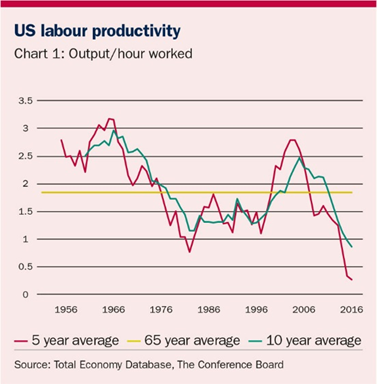

Chart 1, which plots the average pace of productivity growth in

the US over a five-, 10- and 65-year period, demonstrates that

over more finite periods of say five to 10 years there can be

substantial deviations from long run averages. While productivity

averaged 1.8 per cent over the entire 65 year period, during a

five-year time frame, it has been as high as 3.2 per cent and as

low as 0.3 per cent. More generally, we can also see that the

aftermath of productivity surges create exceedingly challenging

backdrops for the economy and financial markets. This has been

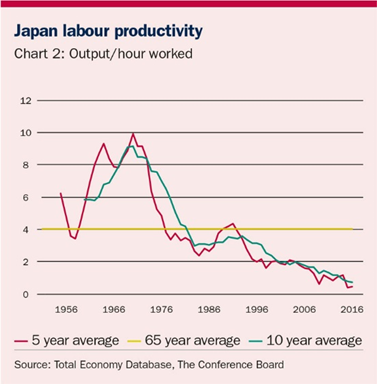

particularly true for Japan - where the country entered a deep

slump following the remarkable productivity surge of the 1970s

(chart 2). Japan has since lost two decades and now

appears to be stuck in secular stagnation.

So, how can we know the type of productivity regime (and

therefore growth regime) we are likely to encounter over the

coming decade? Are there any signposts that can alert us to an

impending shift like the one that Japan encountered?

How to assess a country’s wealth?

There are no easy answers. However, in times of flux and

uncertainty, we believe that it is very helpful to go back to

basics. Given that economic growth, or the flow of output, is

generated by the asset base or the "wealth of a nation",

assessing the asset base of a country can be very useful.

How do we assess the health of a country’s capital base? Smith

defined the capital base as “That part of a man’s stock which he

expects to afford him revenue”. In today’s terminology, this

would include the stock of a country’s physical capital (plant,

equipment, machinery, computers, software etc.), human capital

(education, training), socio-political capital (democratic

institutions, rule of law), natural capital (finite resources)

and financial capital (risk taking and sharing). A smaller asset

base will typically generate a smaller flow of output.

How do "stock" variables in today’s world stack up? Let’s

start with the most easily measured – the stock of a country’s

physical capital. Through time, the flow of output from a

country’s workers has always been proportional to the amount of

physical capital that workers have access to.

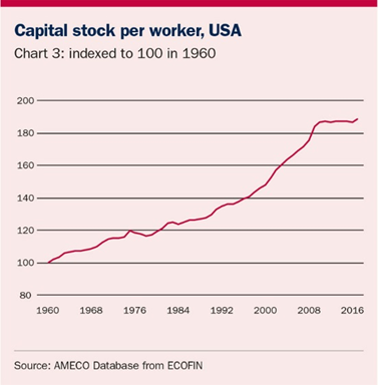

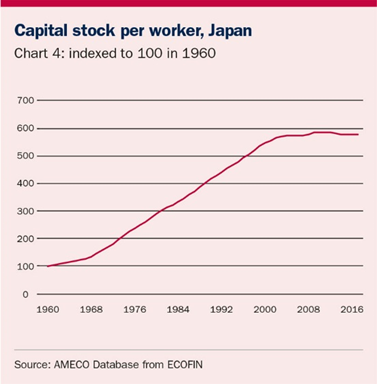

Moreover, a healthy economy is typically one that increases its

stock of physical capital per worker over time. Charts 3 and 4

show the evolution of the stock of physical capital per worker in

the US and in Japan. Since the financial crisis, there appear to

be some dramatic shifts underway. Capital stock per worker, which

had steadily risen throughout the post-war period, plateaued

after the financial crisis and in the US has been stagnating for

about five years now. In other words, businesses appear to have

stopped investing in their workers. This is indeed worrying,

because Japan’s economic stagnation over the past two decades has

been accompanied by a plateau/decline in the capital stock per

worker.

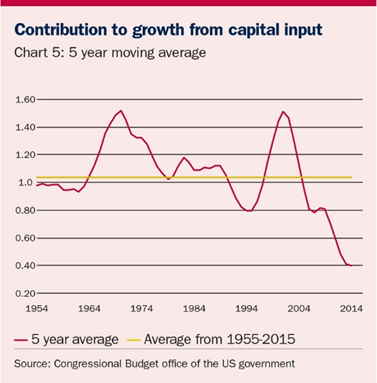

Another marker for evaluating the health of a country’s capital

stock is to evaluate its contribution to growth. In the US, the

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) calculates the contribution to

potential growth from the country’s capital base – it calls this

the “capital input” into trend growth. In Chart 5, you can see

that there have been two surges in “capital input” - similar to

what was experienced by productivity. And in keeping with the

broader productivity data, there has been a dramatic and

worrisome drop off in recent years.

Why are the physical capital bases of advanced economies

declining?

There are possibly two interconnected forces at play

here. First, the demand patterns of post-industrial

societies appear to be shifting away from physical goods towards

services and virtual goods (information, media, data,

entertainment etc.). As demand for physical goods ebbs, so too

has the need for physical capital. If we study the shift in

consumption patterns in the US between 1987 and 2016, in

this 30-year period, 8.5 per cent of the consumer’s wallet has

migrated away from physical goods (cars, white goods, clothing

etc.) towards services which are increasingly tilted towards

information, media and entertainment. Some economists, like Larry

Summers, call this phenomena demassification – or a reduction in

the consumption of “stuff”. The economy as a whole is moving away

from making and consuming goods where it is easier to improve and

measure improvements toward the service sector where it is

exceptionally difficult to increase and measure productivity.

Second, in this post-industrial society, physical capital is

being substituted away by human or intellectual capital. Platform

business models (which often benefit from hyper scale and network

advantages) are increasing the utilisation rates of existing

assets and reducing the need for more physical investments. For

example, ecommerce is continuing to reduce the demand for

shopping malls; platforms like AirB&B and Uber are chipping

away at the demand for hotels and automobiles.

These shifts have been underway for decades and are likely to

endure. As consumption patterns gyrate towards virtual goods and

services, the capital bases of advanced economies are likely to

stagnate and possibly decline. The estimates of productivity and

trend growth are also likely to remain far below long-term

averages.

Assessing the health of the other capital assets that underpin

the economy – financial, socio-political and natural capital -

are big topics in themselves. At a very simplistic level, we can

conclude that financial capital base of advanced economies has

been weakened by central bank intervention, which have distorted

market prices and thereby the efficiency of capital allocation.

The socio-political capital of economies, which have risen

strongly after the end of the cold war, has recently been

besieged by the backlash against globalisation and rising

inequality. The consensus around the political centre is rapidly

disappearing - and with it political stability. Lastly, climate

risks highlight that the natural capital of the world is

precariously balanced and can easily lead to substantial

losses.

In sum, using a “wealth of nations” approach leads us to

believe that there is a strong case for productivity to remain

moribund and for trend growth to weaken. The world economy

appears to have entered a new regime of shifting demand and

challenging fundamentals. Moreover, Japan’s experience serves as

a cautionary tale of how in the absence of another meaningful

innovation wave, we could be entering a period of secular

stagnation.