Technology

A Focus On Native Digital Assets, Smart Tokens

The author of this article, who has already explained broad outlines of the world of digital assets, and dealt with a few misconceptions, takes a look at what are called native digital assets.

In this article, Dr Ian Hunt (more detail on the author below), goes further into the subject of digital assets. (See a previous article from Dr Hunt here.) As this news service knows, digital assets – a term covering various entities – are important for wealth managers to understand. The editors at this news service are pleased to share these insights; the usual editorial disclaimers apply. Jump into the conversation! Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

In the previous

article in this occasional series on digital assets, we

suggested that there were advantages in trading and settlement if

we moved from our conventional representation of assets and cash

into a digital representation.

Our conventional representation of an asset is a depositary

record, exhibiting essentially evidencing its existence, and a

custody record, essentially exhibiting its ownership. Our

conventional representation of cash is as a balance in a bank

account. In the digital world, both are represented by a token on

a digital ledger. A digital ledger is a network of nodes, or

addresses, where tokens are held, the location of a token at an

address evidences title to an asset or cash for the owner of that

address.

When we trade in the conventional world, we generally exchange

assets for cash. The assets are delivered by transferring entries

from one custody account to another, while the cash is

transmitted between bank accounts along separate payment rails.

Both the delivery and the payment are managed in accordance with

settlement instructions provided by the parties to the trade, but

they are separate movements.

In the digital world, trades exchange one kind of token (an asset

token) for another (a cash token) in the same environment – on

the digital ledger. The movements of cash tokens and asset tokens

can be locked together in a process known as “atomic

settlement.” It is perfect “delivery versus payment” (DVP),

which gives certainty to both parties, and removes risk from the

trading and settlement process.

There are other benefits in the digital world.

If the asset, cash, and transaction data is represented in a

blockchain, then its history will be both complete and

unchangeable (“immutable” in blockchain-speak). Attempting

to change data in a blockchain corrupts the entire chain and

makes the data that it contains inaccessible, so fraudulent

manipulation of data is not productive, and it’s obvious when

that it happens.

If the digital ledger is built on distributed ledger technology,

then the nodes share data, in real time, replicating any

transaction that they have an interest in. The DLT ensures that

the relevant data is both visible and aligned between addresses.

This enables the elimination of messaging between the nodes

because they share all of the relevant data. It also reduces or

eliminates the need for reconciliations between different data

stores, because the DLT ensures that their data is maintained in

alignment.

The distributed ledger approach makes fraud much harder because

the data is replicated between nodes. So, any attempt to

change the data at an individual node will be immediately

obvious. A fraudster will need to corrupt all nodes

simultaneously, which is a big ask! To corrupt a

centralised, conventional system, like a commercial bank’s

account ledger, the fraudster must only get access to one

platform. Combined with the immutability and complete history of

blockchain data, DLT shows very significant benefits in security.

This enhances the trust of participants in a digital ledger.

Types of token on a digital ledger

We saw in the previous article that there are four kinds of token

that inhabit a digital ledger. These are:

1. Collateralised cash tokens – tokens giving title to

off-ledger conventional cash or cash-like assets;

2. Collateralised asset tokens – tokens giving title to

off-ledger conventional assets;

3. Native digital cash – currency tokens that exist only

on-ledger and have no off-ledger backing; and

4. Native digital assets – asset tokens that exist only

on-ledger and have no off-ledger backing.

The first two of these (i.e. the collateralised tokens) are what

are commonly described as ‘tokenized’. The word gives it away –

they are conventional assets and cash whose title to ownership

has been represented in token form. The advantages over a

conventional financial ecosystem set out above apply to tokenized

assets and cash, as well as to native tokens, so they are useful

in their own right. However, tokenized assets and cash, and the

collateralised tokens that represent their title, are not the

belles of the ball. Native assets and cash have far more

potential benefit and far greater power to transform the

industry.

What are native digital assets and native digital

cash?

Native digital cash is widely familiar in at least one form:

cryptocurrencies. These are widely discussed, and widely

distrusted because their volatility limits their usefulness as

stores of value and means of exchange. Central Bank Digital

Currency (CBDC) will resolve this issue and give us a native form

of digital cash that can be used with confidence in digital vs

digital transactions and held with confidence as a store of

value.

Native digital assets are much less familiar. They do not rely on

any off-ledger cash or assets as collateral, and their value is

therefore inherent to themselves; where they reference other

entities, these must therefore be tokens on the ledger itself.

Their nature becomes immediately clear if we consider what

happens on a digital ledger. There are really only two things

going on:

-- Value held at nodes/addresses on the ledger in token

form; and

-- Value moving as token flows between the nodes/addresses

on the ledger.

Nothing else is happening, so native digital assets can only

possibly relate to these two. They can either be:

-- A token with inherent value at a node on the ledger;

or

-- An entitlement to a flow of tokens on the ledger.

It is as simple as that.

An example of the former is relatively familiar: Non-Fungible

Tokens (NFTs). These are generally collateralised, and represent

title to an off-ledger asset, like a work of art. However, some

NFTs are natively digital and do not reference off-ledger assets:

they are purely digital artefacts and are therefore genuinely

native digital assets. They have had some moments in the sun, and

are an interesting phenomenon, but they are not going to

transform our industry.

Commitments to future flows of tokens – or “pledges” for short –

are a powerful and interesting form of native digital asset, and

a close relative of the humble IOU.

Far from being an obscure and dangerous phenomenon, pledges are

the building blocks of most of the familiar assets and

derivatives that populate our conventional financial ecosystem.

Think of a bond, a loan, or a swap. We treat them as a single

investable asset (or contract) with terms, conditions, and cash

flows. What they really are is a fistful of pledges, a cluster of

IOUs.

A 10-year, annual coupon bond, for example, has two immediate and

11 future flows. The immediate flows are the payment of cash from

the investor to the issuer of the bond, as principal, and the

delivery of the bond itself to the investor. There follow 10

flows of cash from the issuer, at yearly intervals, as coupon. At

the end of the term, there is a redemption payment of the

principal amount from the issuer to the investor. The flows are

committed by the execution of an order for the bond.

The truth is that there is no coherent thing that is the ‘bond’,

and that is transferred to the investor, distinct from the

obligations of payment undertaken by the issuer.

The title to the bond means nothing more or less than the

entitlement to the flows. There is no risk or value attached to

the bond either, separately from the aggregate risks and values

of the flows. Each flow has a different risk, because it occurs

at a different point in future: the further out it is, the less

likely it is to happen. Each flow should therefore be valued

separately. When we talk about the risk and value of a bond, it

is shorthand for the risk and value of a fistful of flows.

There are, of course, exceptions to the rule that assets are

built of future flow commitments. Purely financial instruments

are, but there are solid physical assets, like buildings,

paintings, and fairground rides, which are not made of flows.

Owning one means that you have title to a physical thing, out

there in the non-digital world. The best we can do with these

assets in the digital world is to tokenize their title,

representing their ownership in the form of a token

on-ledger.

There are composite assets too, where part of the asset is

tokenized/collateralised, and part is represented by future flow

commitments. Equities are a good example, where the owner owns

part of a company, which is an off-ledger, if not physical,

entity. However, ownership of an equity also brings with it an

entitlement to a future flow of dividends. So, an equity, in a

digital ecosystem, is represented by a cluster of tokens: one

collateralised token representing company ownership and one

native digital token representing the dividend commitment.

What happens when flows are primary

Each of our current, familiar asset classes has an associated

issuance model and an associated operating model. Each has a set

of legal terms defining its nature and title, and a set of

regulations saying who can own it and how it is held and

transacted. Each has a set of entities and roles, defining who

must be involved, and how, in safekeeping and transactions in the

asset.

If we treat the flows as the starting point, rather than the

conventional asset, then the world gets very interesting very

quickly.

If purely financial assets are built out of flows, and we define

an issuance and operating model at the flow level, then we could

have a single issuance and operating model across all financial

assets, rather than one of each per asset type. There is also no

limitation on what asset types we can construct: assets and

derivatives are clusters of flow commitments, so we just need to

define a new set of flows, cluster them together, and put a label

on the set, and we have a new asset class. Instead of two to

three years to implement a new asset class, we can do it on the

same day. The financial world can be both much simpler and much

more flexible.

The single issuance and operating models can address much more

than just assets too. Income is just a future flow, and corporate

actions are future flows that may be contingent or elective. An

order is just a back-to-back pair of flow commitments, and an

execution is just the delivery of those flows. An invitation to

trade, or indication of interest to the market, is just a flow

commitment that someone would like to make but hasn’t made yet.

All these fit within the single model too.

A single issuance and operating model across asset types opens

the possibility of a massive reduction in the weight and

complexity of regulation, rolling back what has been seen as an

inevitable and unavoidable tide.

The first big step forward is to see that flows commitments are

primary, and that financial assets are clusters of flows.

Alongside financial assets, we will tokenize any resolutely

non-digital asset, to bring its trading and settlement

on-ledger.

What happens when you make tokens smart

We have an established idea of how systems operate that is so

deeply engrained that we rarely, if ever question it. We see

business systems as the venues where the operations of a business

are codified, and which have the power to make them happen.

Business systems rule the roost and push dumb messages and data

around. Even new developments in DLT essentially follow this

pattern but add tokens to the data and messages that are pushed

around.

If we turn this idea on its head, and make tokens smart and

potent, then the world gets very interesting, very

quickly.

A smart token is a future flow commitment that has knowledge of

the flow that it commits, and has the power to implement it,

without intervention from any human or from any business system.

It is an entitlement with finesse, an IOU with

attitude.

It may sound as if smart tokens are going to be very complex

objects: after all, they are taking the power away from huge and

complex business systems and doing it for themselves. However,

and fortunately, the opposite is true: smart tokens are actually

very simple entities, because of the nature of the digital

ledger. The only thing actively happening on the ledger is the

movement of tokens between addresses/nodes. Therefore, the only

thing that a smart token can possibly do is to move other tokens

(or itself) between addresses. This makes the smart token, the

data that it holds, and the things that it does, very

limited.

A smart token is a token, so it is held at the node of its owner

(who is the recipient of the future flow), like any other token.

It is issued as a pledge by its issuer, who sends it to the

recipient. Again, because the smart token is a token, it can be

fractionalised and traded without limitation, so the recipient

can on-trade it, in fractions or in a cluster with other tokens.

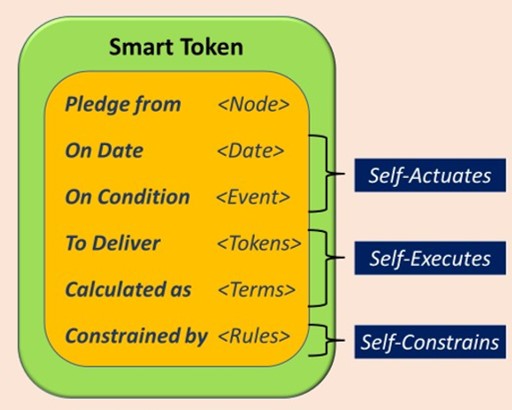

Smart tokens just need to know when to activate and move the committed tokens; what the committed tokens are; how many of them are pledged; where they are to move from (always the issuer’s node) and any restrictions on where they can be held, and therefore where they can be sent to. The smart token doesn’t need to know where to send the committed tokens, as that will always be the address at which the smart token itself is held – the recipient’s own ledger address.

If the smart token knows all this, then it has everything it

needs to move the committed tokens. It just needs the power

to do so, which means that it must be able to take tokens from

the issuer’s node and deliver them to the recipient’s node.

Smart tokens will self-actuate when the timing or conditions for

their activation are met; they will then work out what they need

to do and do it by self-execution. This delivers a level of

automation which is way beyond anything which conventional

business systems can achieve. It replaces all payments,

deliveries, trade processing, settlement management, income and

corporate actions processing, entitlement calculation, registry

maintenance, execution, and order management. The win for

participants in the market is remarkable.

The massive automation achievable with smart tokens significantly

simplifies the single issuance and operating models which are

delivered by native digital assets, will deliver material cost

savings while reducing operational risk, and will foster a

further reduction in the scope and weight of

regulation.

The second big step forward is to make native digital assets

smart and potent.

In the next article in this series, we will look at the

application of smart tokens and native digital assets in funds

and wealth management.

About the author

Dr Ian Hunt is an authority on buy-side business process and

technology. He is a frequent conference speaker and contributor

to industry publications. Dr Hunt has advised many leading asset

managers and asset owners on investment processes, operations and

technology. He is particularly recognised for his work in

promoting innovation in technology for investment. His clients

include M&G, BNP Paribas, Legal & General, Insight

Investment, Fidelity, Hiscox, Threadneedle, Royal London and

Hermes.