Investment Strategies

The March Of The Robots – The Investment View

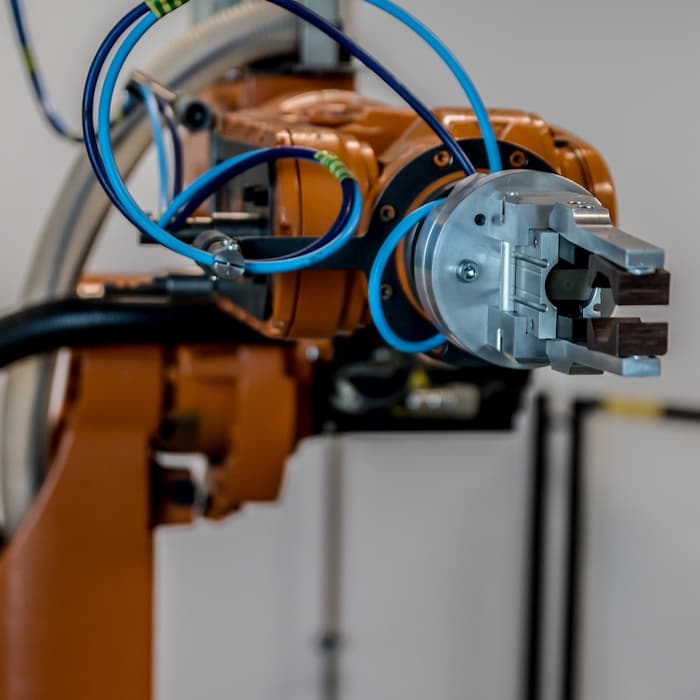

Use of robots is set to continue, even accelerate, but they will create new industries and roles, rather than displacing humans as sometimes claimed.

At the start of the pandemic, some predicted that the rapid rise of robotization would spur chronic unemployment. How come that didn’t happen? To answer the question is Daniele Antonucci, chief economist at Quintet Private Bank. Quintet, based in Luxembourg, is a group of European banks including Brown Shipley, in the UK.

The editors are pleased to share these views and invite readers to respond. The usual disclaimers apply; email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

Robots, generally speaking, are hard to love. While there are exceptions to that rule – think of charming fictional characters such as R2-D2 or Wall-E – we typically recoil from real-world robots because they lack human qualities. They are, quite literally, cold to the touch.

Like technological disruption more generally, including process automation, robots fascinate economists for a host of reasons, most of all due to their impact on employment. In that regard, the key question is whether robots help or harm workers. Are they a complement or a substitute? That is of particular salience in this historical moment, as we consider the pandemic’s impact on employment and try to imagine the post-Covid workforce.

There is a gloomy narrative, which says robots destroy jobs, that has captured the popular imagination for decades. In fact, the fear that new technology will replace human workers can be traced back to the industrial revolution – and even further.

Such concerns may sometimes be wildly exaggerated, but they are not unfounded. A recent McKinsey study suggests that, over the coming decade, some 800 million workers across the globe will have lost their jobs due to automation. Another study, by a pair of MIT and Boston University professors, found that “for every robot added per 1,000 workers in the US, wages decline by 0.42 per cent and the employment-to-population ratio goes down by 0.2 percentage points – to date, this means the loss of about 400,000 jobs.”

A third recent study, this time by researchers at Bocconi University in Milan, looked at European workers’ exposure to automation, specifically robots, and then correlated that to changes in their political views. The study’s bottom line highlights the power of the gloomy narrative and its broader societal implications: exposure to automation led to an increase in support for radical political parties.

When robots come to your workplace and you see a colleague lose their job, that’s a tangible shock. It’s easy to understand why that may lead some to embrace protectionist views. But it is simply not the full story.

Let’s look at this in the context of Covid, then conclude with a much longer-term horizon.

Two years ago, just prior to the start of the pandemic, the world was in the midst of an unprecedented artificial-intelligence and machine-learning revolution. Simultaneously, unemployment rates across advanced economies had risen to all-time highs. Japan and South Korea, where robot use was among the highest worldwide, happened to have the lowest rates of unemployment. Germany, too, had a high degree of factory automation and also low levels of joblessness.

Then Covid struck and unemployment soared. Not since the Great Depression had American joblessness surpassed 14 per cent, as it did in April 2020. Some thought the pandemic would at last prove the doomsayers right, dramatically accelerating the trend towards automation – especially since robots don’t fall ill or spread disease – and spurring chronic unemployment. For the Cassandras, many jobs lost during the pandemic would never come back.

However, such predictions of a prolonged period of very high joblessness simply didn’t materialise. Today, the unemployment rate in the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries, is more or less back to where it was prior to the start of the pandemic. At the same time, the labour-market rebound and accompanying wage pressure – mostly just in the US and the UK so far, and not yet in continental Europe – appear to have further fuelled automation. That includes robotization, which is now more widespread than ever.

Yet evidence of automation-induced unemployment is scant, even as global investment is skyrocketing. The rich world faces a shortage of workers, which is hard to reconcile with the idea that people are no longer necessary. Wage growth for low-skilled workers, whose occupations are generally thought to be most vulnerable to replacement by robots, has been unusually fast.

What’s going on here? The answer is that new technology will inevitably destroy some existing jobs. But it will also help create new ones, including by driving productivity, lowering costs, supporting increased demand and spurring job creation. The historical record is crystal clear in this regard: When overall productivity grows, so does overall employment.

The key word here is “overall.” And therein lies the challenge.

Even if robots do not create widespread unemployment, they can contribute to an environment where the immediate rewards are skewed towards the top. And that is obviously no comfort to those who have lost their job and don’t know where the next one will come from.

At the turn of the previous century, some 200,000 people in England and Wales – representing about 1.5 per cent of the workforce – washed clothes for a living. Those jobs are of course long gone, displaced by the invention of the electric home washing machine. Weavers and typists are likewise now few and far between.

At this unique historical moment, as the world staggers out of

lockdown and into the sunlight, the age-old cycle of innovation,

job destruction and job creation continues. Robots will likewise

march on, replacing some workers and simultaneously supporting

the rise of entirely new roles.

Disclaimer

The statements and views expressed in this document are those of the author as of the date of this article and are subject to change. This article is also of a general nature and does not constitute legal, accounting, tax or investment advice. All investors should keep in mind that past performance is no indication of future performance, and that the value of investments may go up or down. Changes in exchange rates may also cause the value of underlying investments to go up or down.