Emerging Markets

Nikko AM Asks If China Has Outgrown Emerging Market Class

The Japanese investment house, with more than $220 billion of assets under management, asks to what extent that it still makes sense to regard China as an emerging market nation.

A question raised by China’s rapid economic ascent is to what

extent does it make sense to any longer regard the Asian giant as

an emerging market economy? Should it not be put in the same

bracket as developed countries, or is more progress required –

not least the thorny issue of it being still a Communist-run

country, albeit one operating a corporatist sort of capitalism?

These are important questions for asset allocators seeking to get

their portfolio judgement calls right. There’s also the issue of

working out how much of the rest of the world’s markets, and the

Asian region itself, is a reflection of what is going on in

China, as opposed to the US. The rising protectionism of the US

administration of Donald Trump also casts such debates in a

sharper focus than ever before.

In these comments from Yu-Ming Wang, global head of investment

and chief investment officer, International at Nikko Asset

Management, the issues around China’s emerging market status are

put under the microscope.

Since the term emerging markets (EM) was coined over three

decades ago, almost all the underlying facts about EM as an asset

class have changed. Historically, macro views tended to dominate

EM investing more than for developed markets (DM) for a variety

of reasons: 1) Emerging countries experienced a greater degree of

political and economic instability, 2) they were more dependent

on global trade and US monetary policies in the US dollar reserve

system, 3) trade blocs were more isolated with higher barriers to

entry (1), and 4) EM companies were generally younger with

shorter operating histories.

However, globalisation and the transfer of technology have

elevated many EM companies to world class leadership, with

accounting and operational standards aligned to their DM peers.

Access to capital has also become globalised, as these companies

are traded on both domestic and overseas bourses, and the

technology, infrastructure, and governance supporting their

capital markets has had to keep up with the companies they

service.

Along with globalisation, consumer growth has shifted the balance

of economic power. For example, in 1997, DM accounted for 55 per

cent of global GDP to EM’s 45 per cent (2). In 2017, that ratio

was about 41:59 (3). In five years’ time, the IMF projects that

EM will account for 2/3rds of global GDP. How do you justify

calling the lion’s share of the global economy an emerging asset

class?

Currently, EM countries are as influenced by events in China as

much, if not more, as by those in the US. Thus, to successfully

invest in EM, making the right call on China is as important as

making the right call on the US.

The growing impact of China

The current reality is that China is the largest trading partner

to almost all Asian nations (4). China influences the East Asian

EM bloc via direct trade, the IndoChina and Western Asian bloc

via the Belt and Road Initiative, and the resource-producing EM

blocs via its insatiable demand for basic commodities. China

positions its export policy to focus on EMs because of the

similarities between China and EM countries’ consumption needs

and their common inclination for desirable price points.

This EM focus for China’s exports is well-illustrated by Xiaomi

founder Lei Jun, who has named his corporate strategy the

“encircling strategy” (5): first take over the countryside, to

prepare for the final assault on the cities. Xiaomi, Huawei, and

a number of state owned champions’ biggest export markets are

currently India and Russia, then Latam, as they have set their

sights on further global expansion.

Ultimately, we expect EM economies to show a higher correlation

with China than the US. This coupling effect may eventually show

up in equity returns, too (6).

The question of a separate allocation

In the late eighties, debate centred on whether EM should be

treated as an integral part of a global mandate or a separate

dedicated allocation. The debate touches on the question of index

weight being a backward looking or forward looking representation

of the EM asset class’ economic value creation. We believe the

following set of questions were useful guides to such debate:

Will emerging markets generate a sufficiently large economic

growth premium?

Will the asset class become large enough to justify a dedicated

allocation?

Will economic growth support an equity return premium?

Are the skills required to manage EM equities different from

those used to manage DM equities?

Is the correlation to DM low enough to justify a separate

allocation to EM for diversification reasons?

Over the last three decades, the answers to all those questions

have turned out to be a resounding “Yes”, and an overweight

allocation to EM has proven to be the winner in risk/return (7).

That said, success has brought new challenges. Today, the EM

economic growth premium is widely acknowledged, and EM market

capitalisation continues to rise. But what happens when the bloc

of economies that we call EM no longer appear homogeneous?

We think multi-polarity (to borrow the latest buzzword in

geopolitics these days) may be a better way of looking at global

investing than DM versus EM. There are EM markets such as Korea

and Taiwan which are closely linked to global trade, and then

there are those that are linked to commodities and natural

resources. And then there is China, the elephant in the room.

In a hypothetical full inclusion scenario in which China would

account for over 30% of the EM index, we would further argue that

China deserves its own dedicated allocation. We consider the set

of questions above to be as relevant today for the treatment of

China as they were for the debate of EM long ago. We think that a

forward looking allocation to China will serve investors well

into the future, as we believe the answers to the first three

questions on China are all positive, and offer our perspectives

on questions #4 and #5 as follows:

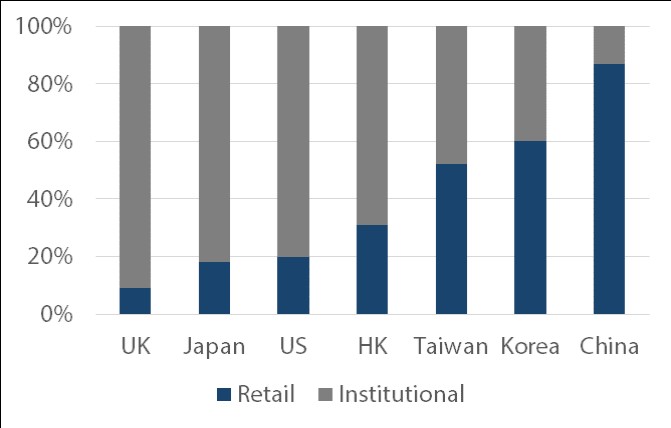

Question #4: China’s high information intensity

The China A-share market behaves very differently from the more

mature markets of Hong Kong and other developed economies. The

A-share market is dominated by retail investors, and the stock

listings are predominantly small and mid-cap companies, as the

charts below show. One conclusion to be drawn from the behaviour

of an average investor in the A-share market is their high

turnover rate and short investment horizon. This phenomenon,

which had been observed in other Asian countries during their

earlier developmental years, presents an opportunity of “time

arbitrage” for investors with discipline and a longer time

horizon. We believe a fundamental research-driven approach with a

long-term horizon is best suited for China’s high information

intensity market.

The value proposition of investing in emerging enterprises, which

are well entrenched in serving China’s billion consumers and

quickly gaining technological edge, is further explored in our

recent paper “China’s Move from Factory of the World to Silicon

Valley of the East”.

Chart 1: Investor mix of China versus DM

Source: JPX, HKEX, LSE, KRX, TWSE, SSE Statistics.

Note: Data as of 2013 for Korea, 2014 for the UK, and 2016 for the rest. Transaction volume basis except for the US (ownership basis).

Chart 2: Market trading value by market cap

Source: UBS, ‘China A-shares – Get Connected’, May 2018

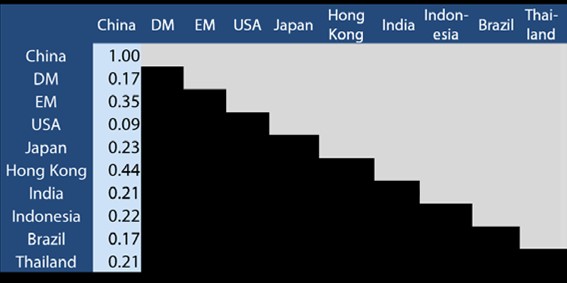

Question #5: Correlation benefits from the A-share market

The onshore market in China is large and can be quite volatile, but it also moves to its own rhythm, thus exhibiting lower correlation to other markets. For an asset allocator, the proposition of higher return and lower correlation is a necessary ingredient for maximizing the diversification benefit from an emerging asset class to expand on its portfolio’s efficient frontier. China’s volatility and correlation to other markets are detailed in the tables below.

Chart 3: Volatility by market

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM, April 2018

Chart 4: Correlation by market

Source: Bloomberg, Nikko AM, April 2018

Looking to the future

Investors everywhere are learning to deal with China. It is big,

it is affecting all aspects of global markets, but it does not

operate according to conventional rules and wisdom developed in a

unipolar world under US leadership. China’s rapid rise from an

emerging market to a developed world power has been difficult to

navigate for all investors. From where we sit, our investment

teams have always considered the rise of Asia and China our base

case.

The question of managing a China allocation as a separate

dedicated mandate or an integral part of a global mandate is

subjective, and dependent on the asset owner’s particular

circumstances. At this early juncture of A-shares’ inception into

global indices, the key question of how, and how much, to

allocate to China should be an active decision not to be

delegated to index makers. Considering the unique profile of the

market and how much China influences the global economy, a

decision about China could be the most important call an investor

can make at this time.

(Parts of this text was presented in a speech at the Pension

Bridge Annual Conference in San Francisco on April 11, 2018.)

Footnotes

1 The global trade-to-GDP ratio rose from roughly 25% in the

1960s to 60% in 2015, according to the World Bank’s World

Development Indicators database.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/06/has-global-trade-peaked/

2 International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook. October 1997.

3 International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook. April 2018.

4 Yu-Ming Wang. The Real Trade War. March 2017. http://en.nikkoam.com/articles/2017/03/the-real-trade-war

5 This strategy was credited to Mao Zedong who seized political power in China by encircling cities via their surrounding rural areas, then capturing them. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-07/10/content_6142547.htm

6 International Monetary Fund. Reserve Currency Blocs: A Changing International Monetary System? January 2018.

7 MSCI. Built to Last: Two Decades of Wisdom on Emerging Markets Allocations. October 2012.