Investment Strategies

Behavioural Finance Tested By Extraordinary Times

The discipline of behavioural finance has evolved over recent years, and the massive economic changes wrought by COVID-19 give examples of how the insights are being put to work in the wealth management industry. There is still big room for development and education, people working in the field say.

Human emotions are being pulled about a lot at the moment, and no

wonder. Consider the following: Market slides, economic lockdowns

and angry words exchanged between China and much of the rest of

the world; daily headlines of COVID-19 deaths, rising

unemployment and cancelled cancer operations.

The upheavals caused by the pandemic have hit people across a

number of fronts, and one obvious result has been the heavy fall

in market indices since the start of the year. The worst of the

rout saw broad indices fall by as much as 30 per cent or more. As

of the time of writing, indices are down by around 15 per cent.

That’s not as dramatic as the 22 per cent fall on the 19 October

1987 stock market slump on a single day. Or, to take another

example, the dotcom era saw stocks crash by almost 78 per cent

from their peak. But even if markets recover eventually,

investors had a rude reminder of how fast things can move. And

because of that, the lessons from a growing discipline known as

behavioural

finance remain hugely relevant.

Behavioural finance tries to delve into the real drivers of human

conduct to understand events such as market booms and busts, why

people can allow biases to lead them into mistakes and other

issues.

A hope that some BF advocates have is that advisors and their

clients will put these insights to work, learning to be more

resilient during tough times and avoid panic and costly errors.

It turns out that the behavioural finance revolution has a while

to run before it becomes part of investors' mental furniture,

however.

"A lot of advisors could have been better prepared than they

are," Greg B Davies, PhD, who works for Oxford Risk, which

delivers insights drawn from behavioural finance for the

industry, told this news service.

Hopefully the COVID-19 saga will give behavioural finance a big

push, said Davies, who before working at Oxford Risk had created

his own consulting firm Centapse, and prior to that, worked for a

decade at Barclays,

heading its behavioural finance team.

Davies argues that while the pandemic has shocked people, it

should not be viewed as a “black swan” event, because the world

has been shaken already by health crises such as SARS, Ebola and

Swine Flu.

Across the Atlantic, Jon Blau of Fusion Family

Wealth, a US wealth manager, said that behavioural finance

“is at the core of our being as a business”.

“We specialise in helping investors learn to make rational

decisions about money under conditions of uncertainty – which is

all the time.” ….”Certainty doesn’t exist anywhere in nature”,”

he said.

In terms of how to prepare clients for a shock, one should think

of it as a lifeboat drill. “You need to know where all the safety

equipment is long before the bow goes into the water,” Blau

said.

Be prepared

The idea of being prepared, of learning how to be “anti-fragile”

(to borrow a term from the writer Nicholas Taleb), is an

important BF building block.

"You need to prepare yourself in advance. You need a contingency

plan. Understand your financial personality," Davies

said.

The tools and approaches that people should have considered in

the good times to prepare for crisis aren't going to be of much

use if they haven't prepared first.

Davies mentioned parallels with how the military thinks about

preparing for stressed situations, such as the idea of

"redundancy", of having people used to doing other persons' jobs

if they need to. A problem is that this sort of "redundancy"

understanding does not feature in a modern, growing free market

economy, with its focus on efficiency and a complex division of

labour.

The key question that many investors and advisors will have is

how to use these insights for their advantage.

"Anyone who is still accumulating wealth has an advantage. They

are not in a hurry and can use this to their benefit,” Davies

said.

If people are still earning they are in a position where they can

invest at lower valuations. Many professional investors, on the

other hand, are forced to trade, so are in some ways at a

disadvantage, he continued.

Another pointer is not to watch short-term market moves but to

concentrate on longer-term goals. Shut out the “noise”, Davies

argues.

Fusion’s Blau concurs.

Blau highlighted the mistake of investors getting out of a

down-market and thereby missing out on any rally, which given

long term outperformance of equities is a classic mistake.

“The question to ask is `what’s the price one needs to pay to

benefit from equity investing' – volatility!” he said.

Blau said that investors make three major errors: Conflating risk

with volatility; sellers of businesses think the task of wealth

management is to preserve capital, but ignore the falling

purchasing power of money, and people think differently about

buying equities than they do when buying and selling decisions

around every other item.

“Investing successfully is a big challenge….there is a tug of war

between one’s faith in the future and fear of it,” Blau

added.

Psychology

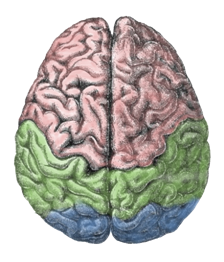

The discipline harnesses what we know about human psychology to

understand that the decisions people make with savings,

investments and spending aren’t as coolly rational and objective

as one might think. Humans don’t, so the argument goes, start off

in life with a mental “blank slate” but instead carry habits and

tendencies that are products of millions of years of human

evolution. (Some of these notions can be controversial – the

field known as evolutionary psychology, drawing on ideas from

Darwin and others, can carry political implications such as

male/female differences.)

It is worth pointing out that it doesn’t necessarily mean that

when a person thinks that they are acting rationally they not

doing so, or that, on introspection, they have acted rationally

and chosen a course of action which is an illusion, like

something out of The Matrix movie. Rather, practitioners in this

area generally seem to argue that the more we know about how we

think, and how we can be biased, that paradoxically the more

rational our choices will ultimately be. For example, a person

who knows that they have a short temper in certain situations

might be more careful about avoiding such situations; a person

with an addictive personality might take care to avoid getting

into environments where temptations exist, and so on.

Terms

The field comes as one might expect with a lot of terms, some of

which explain ideas that seem obvious once they are grasped. For

example, there is what is called “anchoring bias” – the trait of

relying on the first piece of information that is encountered as

a reference point (or “anchor"). Another is “confirmation bias” –

a term relating to the tendency people have to listen to those

who agree with them. “Framing bias”, in turn, is about how people

judge information by how it is presented; a change in how a

problem was framed can cause investors to alter how they reach a

conclusion.

There’s “herding” – we are hard-wired to form crowds – hence

events such as market booms and mass political movements.

“Hindsight bias” explains how people don’t realise they make

mistakes and assume that after something happened, such as a big

spike in the equity market, we knew it all along. So the list

goes on to include notions such as “illusion of control”, ie the

mistaken idea that people have more influence over events than

they really do (as in the idea that people can consistently beat

a market). Other concepts include “loss aversion” (people tend to

hate losses more than they enjoy commensurate gains);

“representative bias” (judging matters by appearance), and

“self-attribution bias” (thinking that good outcomes prove how

clever one is, not thinking of luck. Or, perhaps, arrogance.)