Client Affairs

ANALYSIS: Weavering Capital - The Anatomy Of A Fund Fraud - And The Lessons

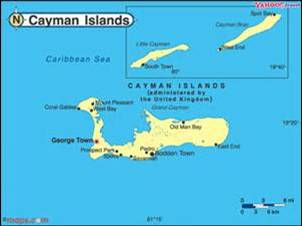

The Weavering fraud case in the Cayman Island is an object lesson in the mistakes people can make in exposing themselves to loss and fraud. This article goes through the kind of checks investors - and their advisors - should make.

Chris Hamblin, editor of Offshore Red and Compliance Matters,

two sister news services to this one, writes about one of the

most important legal cases involving the Cayman Islands to have

taken place in several years. Whenever large crimes are unearthed

it inevitably prompts soul-searching among industry

practitioners, not to mention wounded clients, of how they

managed to miss the fraud and what must be done to prevent such

larceny happening again.

It was in January this year that Magnus Peterson, 51, the head of

Weavering Capital, one of the most popular hedge funds in London,

was convicted on several counts of forgery and fraud. How did he

deceive his investors (a mixture of ultra high net worth

individuals, pension funds and funds-of-funds) and what could

analysts have found out before it was too late?

The Weavering Macro Fixed Income Fund (incorporated in the Cayman

Islands) had total assets under management of $640 million some

time before it went into administration in March 2009. Before

fraud was uncovered, it had been trading for some time and had

been doing relatively well. Eventually, under the helm of

Peterson, it was involved in theft, or at least an abusive form

of fraud or misrepresentation that cheated investors and

ultimately caused the fund to be valued wrongly. Eventually, it

had to close and the investors suffered.

What was Peterson actually doing? A recent briefing from Laven

Partners, the compliance experts and consultants for funds and

investors, looked at the case from the point of view of an

investment analyst. Laven's fund analysts thought that some

tell-tale signs would have been discernible at the time to anyone

who had known what to look for.

Step one: begin with the name

According to the experts, the first step towards an understanding

of what a fund does is to start with its propaganda - what it

says it does. Weavering used words such as “macro” and “fixed

income.” The former typically refers to all forms of economic

influences that might lead the fund manager to invest, while the

latter typically puts one in mind of bonds, or at least some form

of derivatives of bonds and so forth. This is, at first sight and

judging from the name, is what a family office, private bank or

sophisticated investor might have expected Peterson to be doing

as a manager.

Step two: check the financial statements

The next step is to investigate the fund's financial statements,

i.e. to look at what that fund is actually buying. This

particular fund was investing largely in futures. There is

nothing out of the ordinary about this in the macro world; macro

funds often deal in futures. “Fixed income,” however, might seem

to be something of a misnomer. Futures are not fixed income; such

instruments are, instead, likely to be much more volatile and

risky to trade. Risky investments are by no means bad in and of

themselves, but even at this stage an analyst might have

concluded that there was a difference between what the fund was

purporting to do and what it actually was doing. “Fixed income”

tends to suggest a regularity of return and a low risk.

Step three: look at service-providers and

capacity

Weaknesses appear when one looks at other things. A look into the

independence of the service providers reveals some conflicts of

interest. Capacity (the total amount of money that can be put to

work with a given manager or strategy without deteriorating the

fund's performance) seems to have been suspiciously low for this

type of fund – Laven Partners put it around the $200 million

mark, commenting that this figure was not common for a fixed

income fund that trades globally.

Step four: look at “margin to equity”

The act of comparing a manager’s margin levels with his total

accounts can give investors a sense of how much risk that manager

is undertaking. The fund sought to limit the “margin to equity”

ratio (which indicates what percentage, on average, of a

commodity trading advisor's managed account is posted as margin)

to 25-40 per cent, which would imply very high levels of leverage

for the type of investments being managed. The due diligence

questionnaire that Peterson provided was very poor and was only

10 pages long.

Step five: look at the human resources

A look at the distribution of personnel at Weavering Capital

reveals another “red flag”: strong overall control by members of

Magnus Peterson's family. This is something that comes up time

and time again in frauds, because family members trust and help

each other. The only way in which an analyst or compliance

officer can set his mind at rest here is to verify the

independence of each family member.

High local expenditure was apparent from the management company

accounts. The acquisition of plush accoutrements for an office is

another sign that things might not be quite right, as a solid

business of this type did not need to spend large sums in that

way.

Lastly, the chief operating officer of the firm was also the

marketing manager and was rarely in office. This, too, should

have been a cause of alarm to investors because the job of COO is

a very important one and nobody who has to spend several days a

month on the road selling the fund can do it well. Investors

should have at least asked Weavering Capital what controls were

in place for those days when the COO was not there.

On the other side of the ledger, Peterson did not lead the lavish

lifestyle of the archetypal hedge fund fraudster. When

investigators looked at his house they found no plush furnishings

and it was valued at £1 million. He did, however, remunerate

himself very generously to the value of £7 million throughout the

life of the fund.

The actual fraud

For years, no actual wrongdoing was apparent. Things finally went

wrong when the main fund in which high net worth individuals had

invested bought a swap (a form of security/investment) which

another company had issued. Weavering Capital Fund Ltd (domiciled

in the British Virgin Islands) was wholly owned by the Weavering

Macro Fixed Income Fund and had issued the swap to the fund. The

court heard that WCF had almost no assets, no independent

accounts and no auditors. In 2011, a Cayman Civil Court ruled

that his relatives, who were on the board of both WCF and the

main fund, were in dereliction of their duties, although nobody

subsequently sought to prosecute them for any crime. One of those

relatives had even forgotten about WCF's existence.

There now began a cycle of conflicts. The main fund had bought an

instrument from a company that it owned. This in itself, apart

from the issues of corporate governance and conflicts of

interest, is not necessarily wrong in the eyes of investors. As a

next step, however, the swap had to be valued somehow. The issuer

valued it, but of course the issuer belonged to the fund.

There was much doubt among investigators about the enforceability

of the swap contracts. On top of this, WCF did not possess enough

in the way of assets to honour its swap obligations. Peterson

said at one point that it had $77 million in assets, but this was

illusory.

Because of the lack of corporate governance and proper risk

management, some people in Peterson's business were undoubtedly

subject to influence - a process that caused the value of the

swap to be increased. By the time everybody realised this and

alarm bells were ringing, it was too late to save the fund

because many investors were by then trying to pull out. Many more

were, of course, trying to remove their money as a result of the

credit crunch of 2008.

Under stress, people who have too much influence over each other

may lead each other to fraud and this is what happened at

Weavering Capital. No one thing that was available to the

scrutiny of investors stood out as totally bad, but the warning

signs were there for anyone eager to carry out a proper

investment appraisal.