Kate Millar (pictured), who is managing director at , presents a strong case for using donor-advised funds (DAFs) arguing that the current UK tax regime is favourable for them. We have carried articles about DAFs and philanthropic structures before (see an example here).

The editors are pleased to share these comments and insights; the usual editorial disclaimers apply. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com and amanda.cheesley@clearviewpublishing.com

The UK’s new tax and inheritance rules have put wealthy families on notice. From April 2025, virtually all long-term UK residents, defined as those present for 10 out of the past 20 years, will face inheritance tax (IHT) on their worldwide assets at the full 40 per cent rate (1).

The Chancellor of Exchequer Rachel Reeves has frozen IHT thresholds until 2030 and even removed the exemption for pension wealth from 2027 (2), driving the Office for Budget Responsibility to estimate that estates paying IHT will nearly double (from ~5 per cent now to about 9.5 per cent by 2030) (3).

In effect, many families face the prospect of losing a much larger slice of their fortunes to HMRC. These changes, coupled with a crackdown on trusts and the end of the non-dom remittance basis, mean that high net worth individuals must urgently revisit estate planning.

Against this backdrop, charitable giving has taken on new resonance. Any bequest to a charity is fully exempt from IHT and, if at least 10 per cent of a net estate goes to charity, the effective tax rate on the rest of the estate falls to 36 per cent. (4) So, a sizable gift to a charitable vehicle can dramatically reduce a family’s tax bill.

Wealth advisors report a sharp uptick in clients asking about philanthropy and legacy planning. In a recent survey, 62 per cent of UK solicitors and financial planners said they expect more estates to include charitable gifts considering the IHT reforms (5).

The proportion of wills including a charitable bequest has indeed been rising from 17 per cent in 2016 to about 21 per cent in 2024 (6) as affluent donors grapple with how to split their wealth between family and causes. In this environment, donor-advised funds (DAFs) have emerged as an especially attractive option. A DAF combines the tax and administrative benefits of a charitable trust with the flexibility to steward a family’s philanthropy over time, effectively helping HNW individuals “have their cake and eat it” when it comes to tax and legacy.

New inheritance tax landscape for the wealthy

The key change for affluent UK taxpayers is that residency now triggers IHT on offshore wealth. Under the new rules, anyone who has been UK-resident for 10 of the past 20 years will be liable on their non-UK assets as well as UK assets (7)

In practical terms, this can sweep in foreign property, overseas shares and trusts that were previously outside the IHT net. Even funds in longstanding family trusts are now exposed as the government insists that “worldwide assets of all UK residents” will be taxed at 40 per cent on death, “even if these are placed in trusts” (8).

This change, projected to raise £12.7 billion ($17.06 billion) over five years from ending non-dom status, is a big shift for globally-mobile families.

Meanwhile, rising IHT revenue targets and stretched budgets mean that HMRC will be watching wealthy estates closely. Savvy advisors know that proactively engaging in complex arrangements (from offshore portfolios to multi-jurisdictional trusts) is now essential. Some families may now prefer to donate assets in their lifetime to avoid tax headaches after death.

Crucially, UK tax law encourages this: gifts to UK charities receive immediate relief. For example, anyone who leaves 10 per cent of their estate to charity cuts the IHT rate on the remainder from 40 per cent to 36 per cent (9).

Even leaving money for good causes overseas can be structured tax-efficiently: UK “Friends of…” charities and DAFs let donors channel funds abroad without losing IHT relief. In short, higher IHT bills mean that estate planners are once again treating philanthropy as a core part of tax planning.

Charitable giving on the rise

There is evidence that these tax pressures are already shaping donor behaviour. A new CAF/Altrata study estimates that the UK’s richest 1 per cent (investable wealth ≈£2 trillion) gave about £8 billion in 2023, roughly 0.4 per cent of their assets (10). By comparison, the wider public donates about 1.6 per cent of income. That gap suggests significant untapped capacity among the wealthy.

In fact, researchers calculate that if UK millionaires each gave just 1 per cent of their assets, an extra £12 billion ($16.07 billion) could flow to charities (raising the total from £8 billion to ~£20bn) (11). The message from the sector is clear: the next generation of donors could increase their support substantially, with savvy tax planning.

Recent data hint that high net worth giving is rising. Between 2020 and 2023, the median annual donation of UK HNW donors (those earning six figures and up) grew fivefold, from about £1,040 to £5,600. Prominent philanthropists have even signed letters urging the government to simplify Gift Aid and promote charitable pledges among the affluent.

In practice, most of today’s wealthy are not yet giving huge portions of their assets. Top earners in 2020 to 2022 donated only ~0.2 per cent of income (about £623 per year for the median high earner). But with more families facing an IHT bill, advisors say a growing fraction of estates will now consider charitable legacies. Charitable giving can be a highly effective planning tool in the new regime, and even those motivated by altruism get a welcome tax incentive boost.

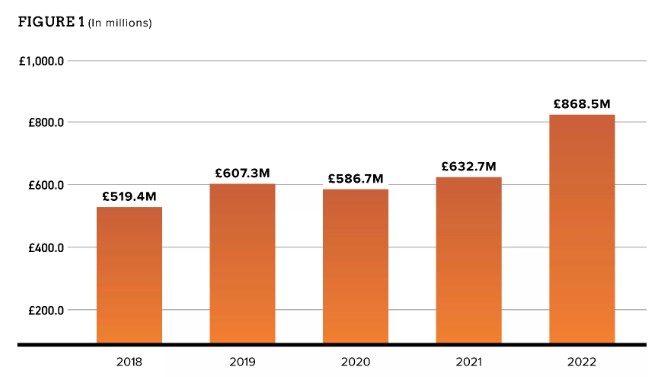

Chart: UK contributions to donor-advised funds have surged in recent years, reaching £868.5 million in 2022 (source: National Philanthropic Trust UK).

The advantages of donor advised funds

So what, exactly, is a donor-advised fund? In essence, a DAF is a charitable “giving account” managed by a public charity (a sponsor) on behalf of the donor. The donor makes an irrevocable gift into the DAF, in cash, securities or even real assets, and immediately enjoys the tax relief on that donation. The sponsoring charity holds and invests the assets; the donor retains advisory privileges, recommending grants to qualified charities over time. (The sponsor handles all due diligence and reporting, and a minimum grant size is typically set by the provider.)

The tax advantages are compelling. UK donors receive Gift Aid on cash contributions (adding 25p for each £1 donated), and higher-rate taxpayers can claim back the extra relief on their income tax return. Notably, gifts of appreciated securities or other assets to a DAF incur no capital gains tax, yet the donor still claims income tax relief on the market value. For example, donating shares worth £1 million can avoid, say, a £200,000 CGT bill (on a typical gain) while generating an income-tax relief at up to 45 per cent, effectively making these a highly tax-efficient transfer into charity. Once in the fund, any investment growth is likewise tax-free.

Conclusion

In summary, as UK tax law tightens its grip on wealth, donor-advised funds stand out as a powerful solution. They protect more of the donor’s wealth (by maximising deductions and growth), channel funds in line with personal values, and insulate future generations from fiscal burdens. For advisors and clients alike, the message is clear: DAFs combine tax efficiency, impact and simplicity in a way that few other vehicles can match. In a new era of inheritance law, they may well be the best tool for preserving wealth and securing a family legacy beyond the probate office.

Footnotes

1, gov.uktheguardian.com

2, civilsociety.co.uk

3, civilsoviety.co.uk

4, charlesrussellspeechlys.com

5, civilsociety.co.uk

6, civilsociety.co.uk

7, gov.uk

8, theguardian.com

9, charlesrussellspeechlys.com

10, civilsociety.co.uk

11, civilsociety.co.uk