While the news agenda can be all too easily dominated by the shenanigans at firms, such as the recent UK “de-banking” fiasco, it’s a relief to focus on trends that don’t tend to show up under bright lights. One trend worth attention is the Japanese economic recovery and the performance of its stock market this year.

As explained in a number of articles on our newswires (see examples here, here and here), Japan appears to be emerging, at last, from decades of stagnant growth, weak share price performance, and a set of “false dawns". The country’s real estate and equity market crashed in the late 1980s and, in spite of a number of fiscal and monetary policy changes, it never managed to get out of its slumber. Add to that an ageing population (the country’s fertility rate is just 1.26), with a relatively tight immigration policy, the underlying picture looked poor.

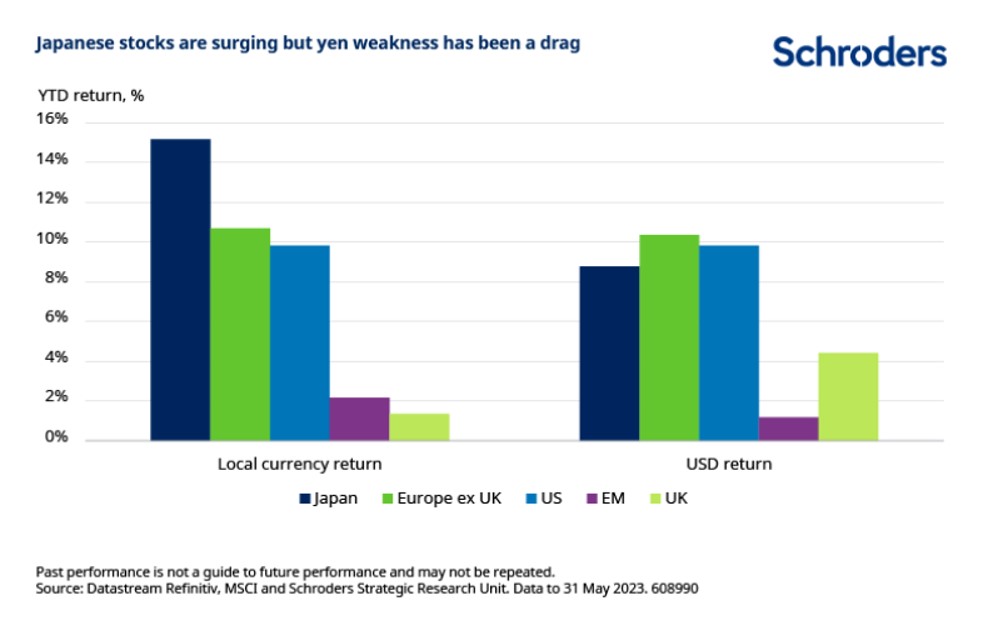

But a series of corporate governance reforms which, in a nutshell, make it easier for shareholders to fire underperforming managers and force them to unlock oodles of cash on their balance sheets, has changed the narrative. When I speak to fund managers, they talk about how the stock market, for example, has far more upside. And, unlike a number of other countries wrestling with inflation, rising prices are – to a degree anyway – positive news for a country that was beset with deflation for the best part of 25 years. The chart below shows that Japanese equity returns have been strong, although the yen has somewhat dragged on performance.

Source: Schroders

A sign of how the mood has changed came from a report a few days ago from Cerulli Associates, the Boston-based analytics and research firm. It showed that European funds have poured billions into Japan. PRs regularly invite me to lunches, breakfasts and dinners (the life of a financial journalist has its upside) to hear about the wonders of Japan’s stock market. In fact I get the distinct impression that wealth managers are scrambling to get on board the “Japan story” before the best valuations have gone. There’s definitely a “fear of missing out” (FOMO) at work here.

Of course, we’ve seen parts of this movie before. And the fear that this revival could be short-lived is, ironically, still a factor gives some investors and fund buyers pause. But it is hard to ignore the drumbeat. For example, over at Schroders, the UK wealth manager, it noted that in late June Japanese shares were “flourishing” and in May, the major equity indices, the Topix and the Nikkei 225, both hit their highest levels since 1989. The firm explains the main reasons: “One is a cyclical aspect, with the Japanese economy being relatively late to reopen after the Covid-19 pandemic. This gives confidence in corporate earnings growth this year, alongside attractive valuations as a whole for the Japanese stock market.

“Secondly, and this is more important as a structural development for the long term, the trigger was the Tokyo Stock Exchange's (TSE) call earlier this year for companies to focus on achieving sustainable growth and enhancing corporate value. This call was particularly directed at companies with a price-to-book ratio of below one,” the firm said.

Schroders, in particular, zeroed in on a metric that explains some of what is going on: the price-to-book ratio. The ratio compares a company's stock price with its book value per share. The book value per share represents the company's assets minus its liabilities, divided by the number of outstanding shares.

“There are a lot of companies listed in Japan with P/B ratios below one. That means there are lots of companies with the potential to be revalued more highly – if they can convince investors that they should be,” the firm said in its note. And there are ways of raising that ratio, such as pushing forward research and development and investing in human capital, thereby boosting growth; they can also boost shareholder returns by buying back stock or hiking dividends. And there are signs, Schroders said, that Japanese firms are taking the hint. The percentage of companies that are “net cash” (i.e. whose cash on the balance sheet is greater than their liabilities) is 50 per cent. That gives those companies scope to invest in their business, or increase returns to shareholders, or perhaps both.

Of course, it is important not to get carried away. If the Japanese yen weakens, for example, it means that non-yen investors who gain from a rally in stocks get hit on the forex effect. Japan is not an easy country to invest in if one strays outside the field of the big caps – many of its companies aren’t tracked by analysts, although the very fact of the market’s revival might change that.

But there are reasons to be more optimistic. Anyone who can speak fluent Japanese and understand stock market investing is in an interesting position. Japan earns a lot from Chinese markets and the re-opening of mainland China after the pandemic is a positive development. Also, given interruptions to supply chains and US trade tensions with Beijing, there's a natural desire for alternative sources of supply, and Japan is an obvious candidate, along with India.

I am just about old enough to remember the mid-1980s and the tremendous success and vigour of Japan’s economy. (Suddenly, Hollywood movies had a lot of themes about Japan.) Japan’s manufacturing sector, for example, was the toast of the (often resentful) West. Its brands were household names. People such as Soichiro Honda, for example, were equivalent to the Rockefellers, Musks or Carnegies of the West. Qualities such as precision, attention to detail, as well as prowess in fields such as robotics, count for a lot – and Japan has these qualities. With AI all the rage, the country is surely in a good position to tap into that as well.

All the usual caveats and health warnings apply – I am a journalist, remember! – but it does look as though, for the time being at least, Japan is a country worth paying close attention to.